It’s been two years since I started working full-time on pyOpenSci

I have been working full-time building pyOpenSci for two years now, thanks to funding from the Sloan Foundation and CZI (Chan Zuckerberg Initiative). pyOpenSci has come SO FAR in two years.

It’s time to take a breath and celebrate everything the pyOpenSci community has accomplished. Before we move on to the next big thing—our pyOpenSci Fall Festival (more on that below)—I want to take a moment to reflect on:

- where we’ve been,

- what we’ve accomplished, and

- the incredible community of practice that we’ve built.

I’ll wrap up by discussing what’s next for pyOpenSci.

A brief history of pyOpenSci

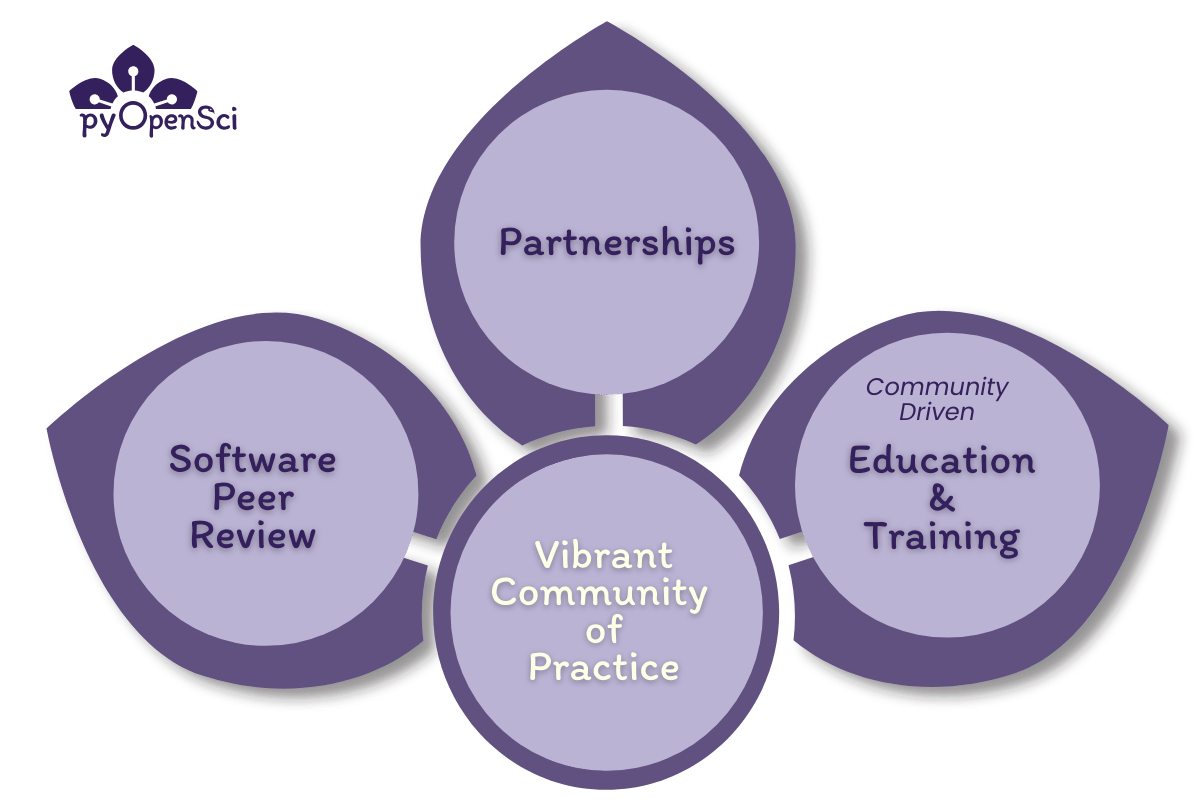

I founded pyOpenSci in 2018 because I saw the pain points that scientists were facing in creating open, reproducible workflows using Python. My experience inspired me to establish a vibrant, inclusive pyOpenSci community of practice fueled by making open science best practices more accessible to scientists.

pyOpenSci makes open science more accessible by developing educational resources, running training events, running an open software peer review process and partnering with other communities. From humble beginnings characterized by small community meetings, pyOpenSci has blossomed into a thriving community marked by:

- a robust editorial team,

- hundreds of contributors, and

- numerous valuable community partners and friends.

Our software peer review program has seen over 50 packages; we’ve accepted 35 scientific Python packages into our growing library of trusted scientific Python packages and have 17 packages in active stages of review as I write this post.

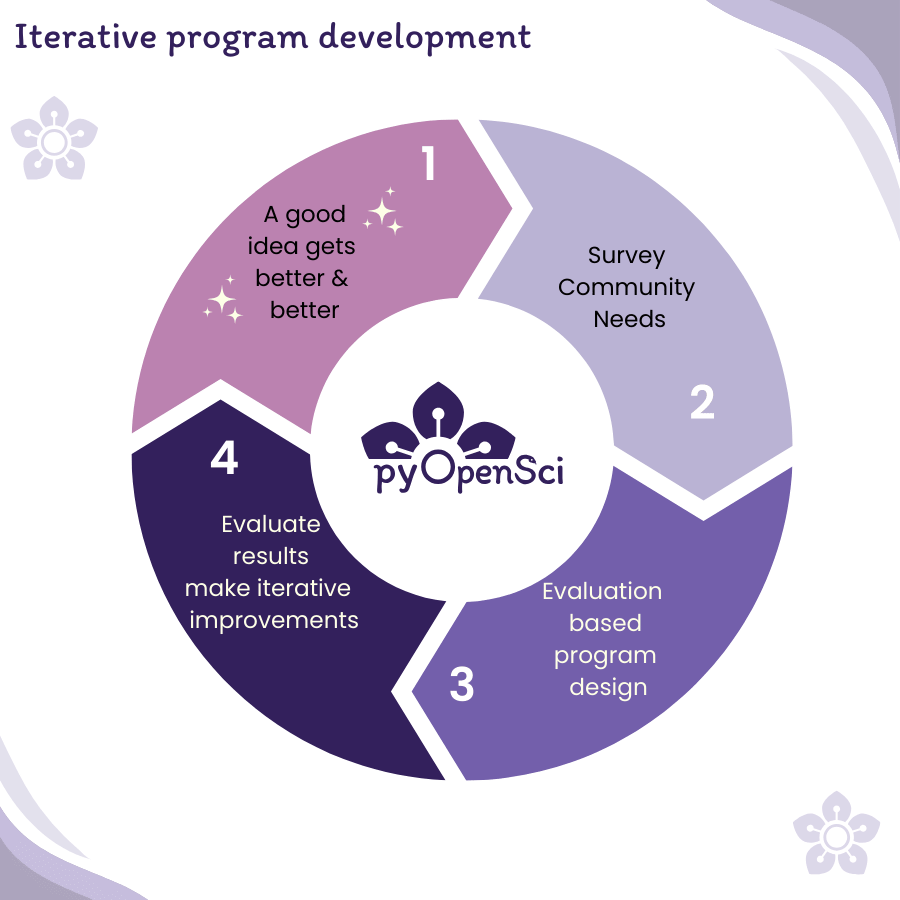

pyOpenSci and iterative, data-driven program design

pyOpenSci’s development and design is data-driven. I collected survey data from scientists and Pythonistas at meetings and conferences to identify community pain points and needs. I used this data to inform the iterative development of pyOpenSci programs, events, and resources and to define pyOpenSci’s mission, vision, values, and structure.

The survey data I’ve collected shows what I’ve seen in the classroom– scientists face many challenges when processing, analyzing, and sharing their workflows. While reproducible science is critical to accelerating science, sharing and publishing code is hard.

This blog post includes quotes and data I’ve collected over the past 5+ years; these data have shaped the vibrant community of practice that pyOpenSci is today.

Responses to the question: How could pyOpenSci help you with your science, code, and software?

[*I want to know...*] What are the best practices for sharing the code?

[*I want to... *] Streamline the development of good quality, socially responsible, and easily shareable software.

[*I want more *] Bullet-proof, well-documented packages for Earth science.

Many earth scientists attend AGU. It’s a different crowd than who you meet at the SciPy meetings.

Why pyOpenSci tackled Python packaging

pyOpenSci’s design is also based on our experiences developing software peer review guidelines for Python packages. We interact daily with scientific software maintainers. According to our surveys, 80% of our maintainers and reviewers identify strongly as scientists.

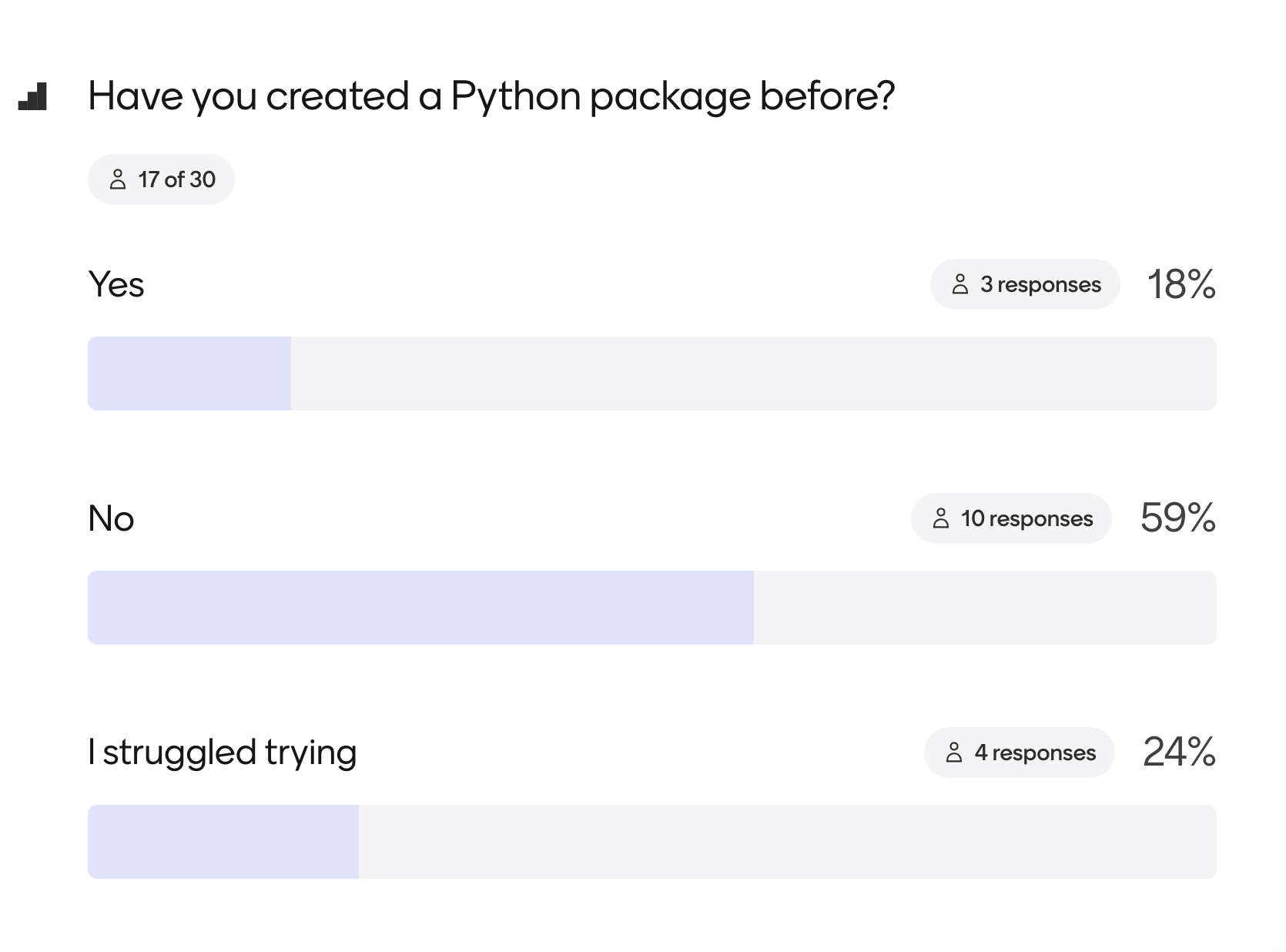

As we developed our peer review guide, it became clear that a beginner-friendly packaging guide was essential to support scientists in sharing their code because:

- Our pre-review software checks require basic package infrastructure. Scientists must be clear about the core elements of a Python package.

- We want to help scientists make their packages more maintainable over time by adding tests and continuous integration (CI) checks that run when someone submits a suggested change (or a pull request). We want to set scientists up for success.

- We realize that Python packaging is a thorny ecosystem to navigate. I knew that pyOpenSci could help file down those thorns.

“How could pyOpenSci help you with your science, code, and software?”

Training for people who can code for themselves but want to start developing software for others. Topics include style, documentation, testing, git, etc.

Helping scientists navigate a complex and difficult-to-understand Python packaging ecosystem

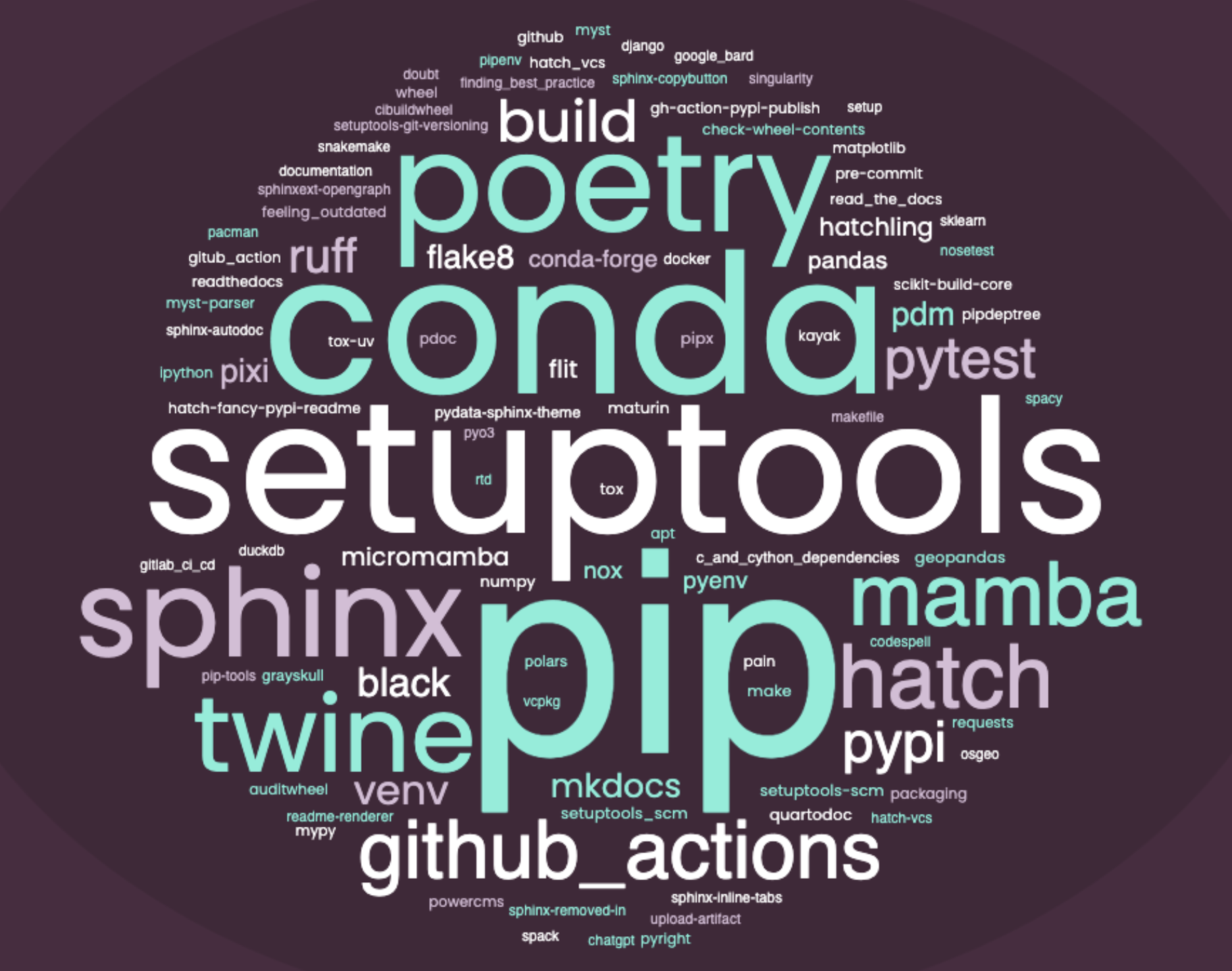

The packaging ecosystem has evolved rapidly. Numerous tools and approaches are available to create Python packages. Further, recent changes to ecosystem standards have led to an explosion of packaging tools like Hatch, Flit, PDM, and Poetry; other tools like Pixi and Rye are also on the horizon. Scientists often feel overwhelmed by the sheer number of options and have begged for clear guidance for years.

QUESTION: "How could pyOpenSci help you with your science, code, and software?"

[*I want pyOpenSci to*] clarify Python packaging. There are too many different mechanisms floating around...

There are some excellent, more advanced guides and tutorials available now, such as PyPA’s packaging tutorial and the scientific Python development guide. However, our resources serve a different audience.

- The people using our resources are often folks who find the packaging ecosystem to be overwhelming.

- Scientists are also only sometimes familiar with various terms. For example, it’s easy to confuse a build backend with a build frontend, especially when both have the word “hatch” in them (e.g., Hatch vs. Hatchling).

- Scientists often want to avoid deciding what tools to use. pyOpenSci intends to alleviate this burden and provide a robust and practical approach.

From a beginner’s perspective, every decision is a potential opportunity to go down the wrong path, adding cognitive load. Armed with a clear understanding of the packaging pain points, I knew that pyOpenSci could simplify the packaging journey for scientists.

If you want to learn more, my talk at PyCon dove into the Python packaging challenges of too many options and cognitive overload.

pyOpenSci guided the community towards a single way to create a Python package in under a year

In just under a year, pyOpenSci created a comprehensive packaging guide that includes an end-to-end Python packaging / share your code tutorial that walks scientists through creating a package and publishing it to both PyPI and conda-forge using Hatch. Together, the pyOpenSci community built consensus around which packaging approaches should be adopted as best practices. Building consensus around packaging decisions was challenging, but we were successful because we focused on our users first. We decided on which tools we thought would create the best packaging experience for scientists creating pure Python packages.

Check out the GitHub pull requests for packaging guide pages if you’re curious about the feedback and discussions that we had when writing the packaging guide. Notice the number of comments on the most popular PRs. The sheer volume of comments on some of the early PRs associated with packaging build tools speaks to the various issues, complexity, and decisions we needed to make.

Building Python packaging consensus and developing the pyOpenSci Python Packaging Guide

The success of our Python Packaging Guide is due to extensive community input. We directed Python Packaging Guide contributors towards the objective of simplifying Python packaging for beginners. Focusing on a specific audience allowed contributors to make decisions about the content in the Guidebook more easily. It also ensured that the outcome text is easy to understand for beginners and for scientists who prefer to avoid delving into packaging nuances. In each review, we made sure to include a diverse group of reviewers, including:

- packaging tool maintainers: We asked each maintainer from Flit, PDM, Hatch, and Poetry to provide feedback on our overviews of their tools,

- PyPA members who have already developed packaging resources that serve the broader Python community,

- core scientific Python community members who are maintaining tools like Matplotlib, Numpy, and Pandas that require more technical complex builds, and

- scientists with varying levels of packaging expertise: This group is most important as packaging beginners provide the lens of what is confusing and ensure that the technical content is more beginner-friendly. The truly collaborative effort of creating the Python Packaging Guide resulted in a beginner-friendly and accurate guide that the pyOpenSci community now maintains and continuously updates.

It was essential to have a mix of content reviewers with a range of packaging expertise to make the guide accurate and accessible. Some were packaging experts building packaging tools, and others were beginners, the audience for whom we wrote the guide.

What’s in the pyOpenSci Python Packaging Guide?

The pyOpenSci packaging guide provides an overview of the Python packaging ecosystem to support users who want to understand the packaging landscape. These users may want to decide on their own which tools best serve their needs. The guide also defines core packaging terms that can make the ecosystem seem more complex than it is, such as:

- build backend,

- build frontend,

- wheel, and

- sdist.

Our Python Packaging Guide aims to translate the technical jargon that gets in the way of new users having a successful packaging experience. Over time, we hope that this will make packaging less confusing and more accessible to more people.

Creating opinionated Python packaging tutorials

In addition to the ecosystem overview provided in the guide, I knew that we needed to have opinionated, complete Python packaging tutorials that guided users through the entire packaging process including:

- creating a package,

- publishing it on PyPI, and

- conda-forge.

Most scientists (and packaging beginners) want to get the job done; they don’t want to become packaging experts. A community presenter made this statement directly at the PyCon US 2023 Python packaging summit:

I just want to create a Python package. Where is the tutorial or documentation that teaches me how to do that?

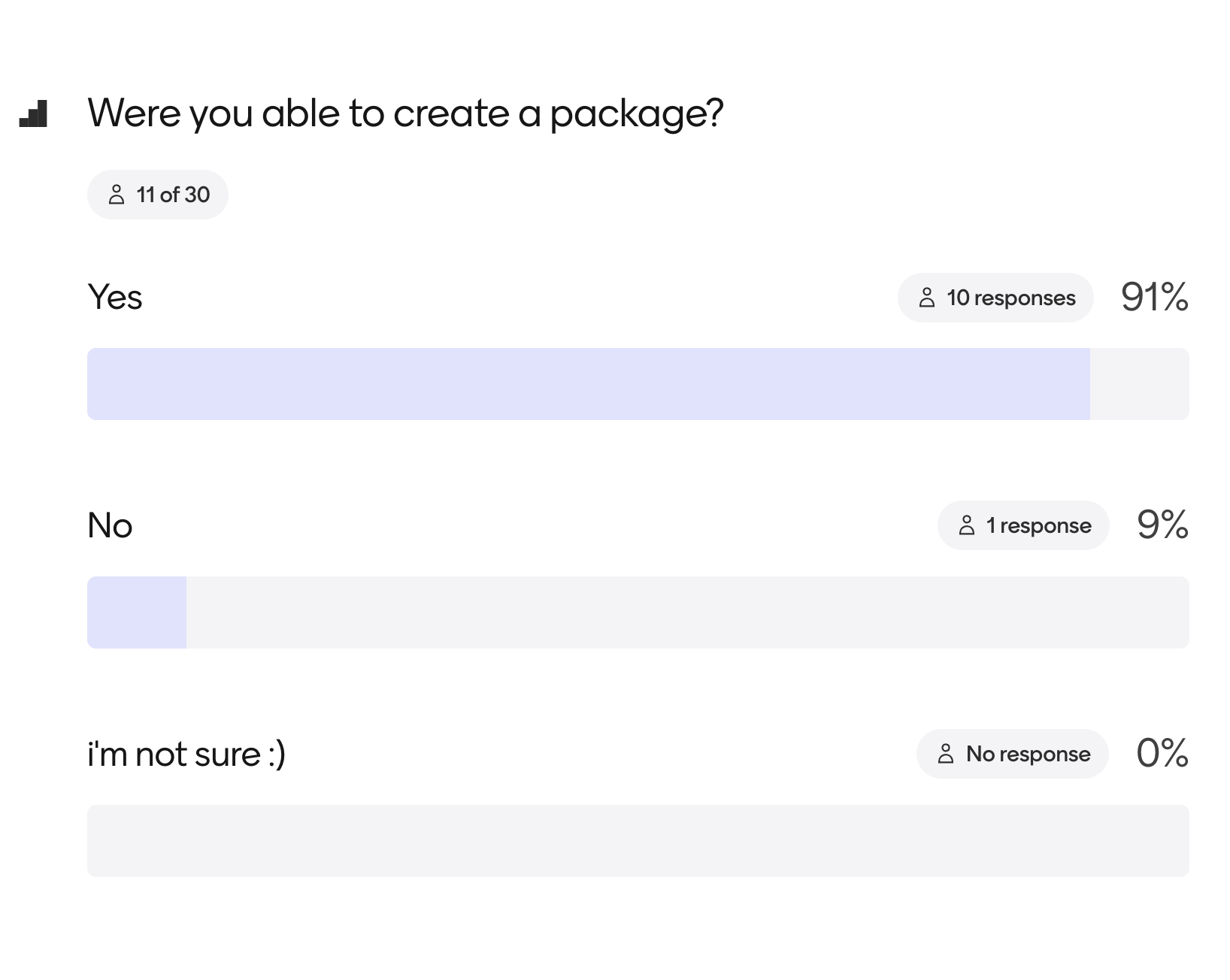

Our Python packaging tutorials went through the same community development and review process as the rest of our Python Packaging Guide. We have also begun teaching the lessons; most workshop attendees have successfully created their first Python packages!

Teaching online lessons is the best way to ensure they stay current

I have created hundreds of open online lessons both for ecologists NEON and earth and environmental scientists. One of the biggest challenges is that it’s easy for data science lessons to become dated quickly–especially in the rapidly evolving data science space. By teaching the lessons, we can update them regularly as the ecosystem evolves. We also often have users review the lessons at our annual sprint events to test them out; more on pyOpenSci beginner-friendly sprints below.

Hi Leah. Thanks for the course today. I really enjoyed it. I heard about it from your post here in the Python channel so I'm glad you shared it here. I'll keep my eye out for more coming up and will be referring to the tutorials and guides on your site. Hopefully you work out the spatial chat because that seemed to have a lot of potential! I also want to let you know that I got a ton of value out of your materials on the CU Open Earth data analytics site, and it's still my go-to resource to point people to when they ask me how to get started learning the open source spatial stack. So thank you!

In addition to the valuable feedback we receive from our community, the data we collect through Matomo web analytics shows our guide’s usage and growth. I will leave web and social media growth, which have also shown extraordinary growth for future posts!

The power of community: Translating the guide & tutorials to other languages

The success of our packaging guide has been remarkable, thanks to the tremendous input and feedback from the community. What began as a simple guide has evolved into a collaborative project, with enthusiastic participation from contributors worldwide.

@leahawasser @pyOpenSci clicking through and eventually found myself looking at 'what is a Python package' and involuntarily performed a standing ovation. bookmarked it as an example of great docs for an incredibly complex subject with many meanings in many different contexts

At our last PyCon sprint, a then-new contributor, Felipe Moreno, set up translation infrastructure for our guide. The translation infrastructure uses a Sphinx extension that allows contributors to translate as much or as little of the guide as they wish. This process supports small iterative pull requests that any contributor with little time can make.

#: ../../documentation/hosting-tools/intro.md:3

msgid ""

"The most common tool for building documentation in the Python ecosystem "

"currently is Sphinx. However, some maintainers are using tools like "

"[mkdocs](https://www.mkdocs.org/) for documentation. It is up to you to "

"use the platform that you prefer for your documentation!"

msgstr ""

"Sphinx es la herramienta más común para construir documentación en el "

"ecosistema de Python. Sin embargo, algunos mantenedores están usando "

"herramientas como [mkdocs](https://www.mkdocs.org/) para generar la "

"documentación. ¡Es tu decisión usar la herramienta que prefieras para tu "

"documentación!"

Felipe’s translation infrastructure contribution has sparked significant community momentum. As I write this, pyOpenSci contributors are actively translating our Python Packaging Guide into Spanish and Japanese; we have had dozens of pull requests. One contributor may even teach the pyOpenSci Python packaging lessons at PyCon Japan next year! This entire effort underscores the power of community when guided in the right direction.

Our guide is becoming a global resource!

You may be wondering where all of these new contributors are coming from. We get many new active contributors when we lead events at core meetings.

I’ll talk about that next.

pyOpenSci at PyCon and SciPy 2024 – sprints, talks and new contributors

Sprints are one of my most favorite types of events to hold because they involve this cool mix of learning, helping and community.

pyOpenSci sprints at Python meetings

We started holding sprints at PyCon US in 2023. Engagement at pyOpenSci sprints has grown significantly since we started leading these events. This year alone, we engaged with over 50 contributors at sprints who have submitted 86 issues and pull requests!

What is most impressive is many of our sprint participants have continued to contribute to pyOpenSci after our in-person sprint events.

While pyOpenSci operates mainly as an online community, I find there is no better way to build a core community than by holding in-person events at large meetings. While we get plenty of expert Pythonistas at our sprints, our sprint events are always beginner-friendly. Many first-time contributors help pyOpenSci with various open issues on our help-wanted GitHub project board while submitting their first pull requests and issues to GitHub.

pyOpenSci beginner-friendly sprints help us and also the community

Beginner-friendly sprints represent a true win-win for both contributors and pyOpenSci. Contributors learn new skills, and pyOpenSci gets help with the vital work that we are doing.

What is a community sprint?

Community sprints are collaborative coding and documentation update sessions where new and experienced contributors work together on open-source projects. These sprints provide a supportive environment with guidance from project maintainers or experienced developers, helping participants contribute effectively. They are an excellent opportunity for learning, networking, and making meaningful contributions to the open-source community. You can read more about that here.

| Year | PRs & Issues | Contributors |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 41 | 12 |

| 2024 | 86 | 39 |

My talks at SciPy and PyCon US 2024

Last year, I gave a talk at PyCon US at the Maintainers Summit. This year, I gave talks about both SciPy’s Maintainers Summit and at PyCon US - in the main track! At PyCon, I spoke about how pyOpenSci is leveraging the community and building consensus on the thorniest topic: Python packaging. At SciPy, I focused on bringing the scientific community together to help solve Python packaging. I also overviewed our community-run scientific Python software peer review program and the success that we’ve had collaborating with other partner communities, such as Astropy.

Here is my SciPy video if you want to check it out now. :)

pyOpenSci’s software peer review program is growing, too

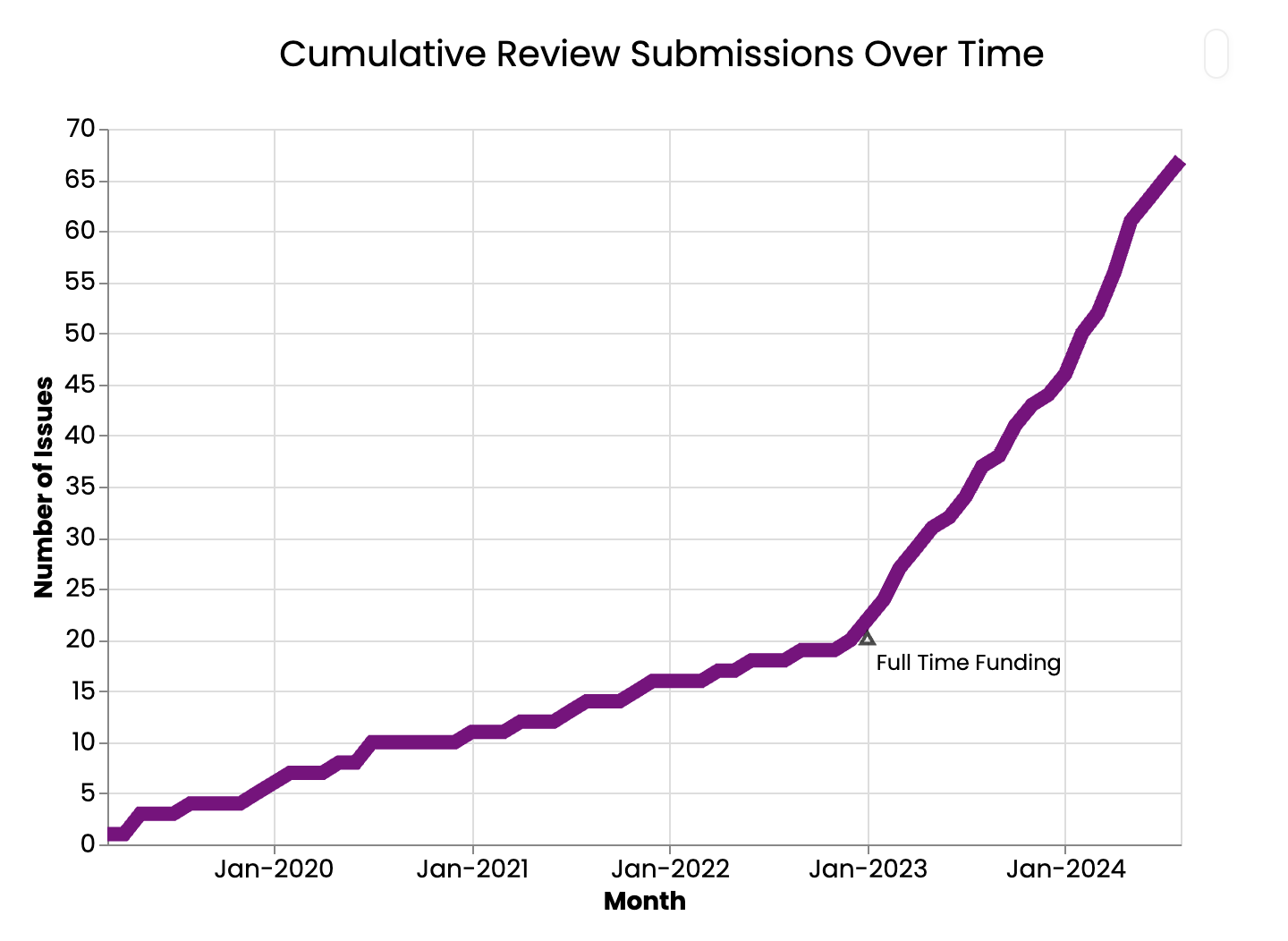

Funding has propelled pyOpenSci’s peer review process forward. While pyOpenSci has run peer review since 2019, funding allowed us to document, formalize, and make the peer review program more sustainable and scalable. The peer review guide was one of the first things I worked on in the Fall of 2022. The goal of this guide was to define each role in the software peer review process, define policies around our review package scope, how we review, how we determine what is in scope, and more. The guide also documents our community partnership program, which we launched in 2024 through our collaboration with Astropy.

In four months, we published a shiny new peer review guide. In January 2023, we re-launched peer review again. Peer review submissions increased dramatically starting in January 2024 (see below).

Is pyOpenSci’s peer review program diverse?

Diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) are core to everything that pyOpenSci does. But how do we know that we are aligning with that core value?

Data can help us here, too. Here are a few insights from 93 people who have participated in our peer review program survey over the past two years. Our peer review participants represent a healthy mix of students, industry professionals, and academics.

Almost half of the participants identify as having some computer science application in their work; 80% self-identify as scientists (as mentioned above).

About 40% of our peer review participants identify as female, non binary, or non conforming.

Open Source metrics

Some of the open-source responses surprised me:

- 60% of people maintainers have funding to do their work! (This number surprised me given the challenges I have seen in funding open source work.), and

- 70% of maintainers report that outside contributors contribute to their projects through issues and pull requests.

I’ll dedicate another blog post to examining this data more thoroughly. Still, you can get the gist from the above summary: We have a strong representation of people from different career stages. However, we still need to do more to support increased gender and identity diversity.

A thoughtful, kind, and supportive community is what makes pyOpenSci special

Every morning, I wake up and am excited to begin my work. It doesn’t matter if I’m working on budgets and other Executive Director-type tasks or developing educational content and teaching (my two favorite things); I can’t wait to see what messages pop up in my inbox, be it Slack, email, Discord, or GitHub. I love my job because the pyOpenSci community is extraordinary.

People care about our organization’s mission to help scientists make their science more open and collaborative. So they can solve the world’s greatest challenges.

The community wants to help–be it each other or pyOpenSci as an organization.

The community is kind; the discussions are engaging and people help each other.

I love the friendliness and positive energy around the combination of science+computing (in Python, too)! It's a lovely community of practice!

The community also cares a lot about the scientific Python ecosystem and wants to see more robust software.

As maintainers of the Scientific Python library, we see great potential in pyOpenSci. Test, code, documentation, and internationalization. These are things we have gradually accumulated know-how for in order to create a robust library on GitHub. Now, these are about to be integrated by the pyOpenSci project.

They care about the packaging guidelines we have worked so hard to co-create and the impact those guidelines and online resources have on scientists who are just trying to get their jobs done.

I'm hopeful that the standards established by pyOpenSci will help alleviate the reproducibility crisis, increasing public trust in science, accelerating progress, and making all our jobs a little bit easier!

And, like me, the community cares deeply about education. The community wants to help eliminate the packaging and open science thorns. They want to make packaging (and using Python) more accessible to more people.

I love the educational aspect of pyOpenSci and how it focuses on removing the technical friction that prevents people from contributing to open source and open science. The community makes a conscious effort to create a welcoming culture and provide a safe place to learn for beginners. It helps prepare people for even bigger future contributions to the open science and open source movements.

Carol below was more than just a participant! She also helped many students in their workshop learning experience.

As a participant in the first packaging workshop, I found that individual attention and focus on success were outstanding. The organization and approach to teaching a scientist how to create a package helped build skills and ongoing productivity.

Building a sustainability model for pyOpenSci so we can continue to thrive - what’s next

There’s a strong demand for the work pyOpenSci is doing. Still, every nonprofit or fiscally sponsored project has to ask:

How do we keep this going long-term?

Writing grants to bring in funding is essential, but I need to do more than just write grants. Writing grants takes tremendous energy, with only a ~10-20% chance of success. Also, grant calls usually focus on innovation. They do not often support project maintenance and daily operations.

To ensure that pyOpenSci is sustainable, we’re rolling out paid online training events. Paid events are a revenue model used by other nonprofits in our ecosystem:

NumFocus runs PyData and SciPy meetings The Python Software Foundation runs PyCon as a significant fundraising event. These paid events will support the low-cost training, event scholarships, free online tutorials, and resources we will continue to create and publish online.

What’s next for pyOpenSci - The Road Ahead

Our next training event is the inaugural pyOpenSci Fall Festival–a week-long event that teaches skills needed to:

- write cleaner, more modular code,

- package and share code,

- publish and cite code, and

- create reproducible reports that connect code, data, and outputs into a dynamically produced interactive publication.

We also will develop collaborative GitHub lessons following the BSSw fellowship I received this year.

Connect with us!

There are many ways to get involved if you’re interested!

- If you read through our lessons and want to suggest changes, open an issue in our lessons repository here

- Volunteer to be a reviewer for pyOpenSci’s software review process

- Submit a Python package to pyOpenSci for peer review

- Donate to pyOpenSci to support scholarships for future training events and the development of new learning content.

- Check out our volunteer page for other ways to get involved.

You can also:

- Keep an eye on our events page for upcoming training events.

Follow us on social platforms:

If you are on LinkedIn, check out and subscribe to our newsletter.

You can also:

- Check out our Python Package Guide for comprehensive packaging guidance

- Keep an eye on our events page for upcoming training events

About Me

My name is Leah, and I’m the executive director and founder of pyOpenSci. I have over 20 years of experience in both academic and nonprofit spaces and have dedicated my career to helping scientists overcome the challenges of open science. I’ve built and led two successful data science programs:

- NEON Data Skills Program at NEON, and

- Earth Analytics Program at CU Boulder.

I’m now building pyOpenSci–a vibrant, active, and diverse community of practice that supports open science and the open-source software that drives that science.

The programs I build have consistently stayed at the cutting edge of technology through continual evaluation and a data-driven approach. Throughout my career, I’ve observed significant gaps between the innovative tools being developed and the training scientists receive, which has driven my work in bridging these gaps.

Connect with us!

There are many ways to get involved if you’re interested!

- If you read through our lessons and want to suggest changes, open an issue in our lessons repository here

- Volunteer to be a reviewer for pyOpenSci’s software review process

- Submit a Python package to pyOpenSci for peer review

- Donate to pyOpenSci to support scholarships for future training events and the development of new learning content.

- Check out our volunteer page for other ways to get involved.

You can also:

- Keep an eye on our events page for upcoming training events.

Follow us on social platforms:

If you are on LinkedIn, check out and subscribe to our newsletter.

You can also:

- Check out our Python Package Guide for comprehensive packaging guidance

- Keep an eye on our events page for upcoming training events

Leave a comment