pyOpenSci’s approach to beginner-friendly sprints

In previous posts, I talked about:

- Our incredible experience at PyCon US 2024.

- My personal experiences with the Python packaging ecosystem and building consensus within the scientific Python community.

Here, I will share with you what we have learned at pyOpenSci through holding beginner-friendly sprints over the past two years. Specifically, I want to explore the varied motivations and barriers associated with contributions to open source, and how pyOpenSci is addressing them.

TL;DR

- I believe that we can get more people involved in Open Source if it’s done the right way. Despite the word “open” in the name, open source is not necessarily open to all people.

- By setting up infrastructure such as project boards and tagging issues as beginner-friendly, you are on your way towards a beginner-friendly sprint.

- Be prepared to support people who are newer to Git and GitHub.

- Create opportunities for beginners to contribute to documentation. The beginner lens reviewing your docs is critical to ensuring the documentation is usable! Documentation contributions can also be implemented entirely on GitHub without needing to use the command line.

PyOpenSci’s PyCon US 2024 sprint

I’ve been running pyOpenSci sprints for about two years now. This year was my second year leading a PyCon US sprint for pyOpenSci. I’ve learned a lot! While last year we had two sprinters, this year we had a tremendous turnout of 18 people from several countries and across the United States for our 1-day sprint. This resulted in over 35 issues and pull requests, where volunteers helped fix issues on our website, in our tutorials, and in our packaging and peer review guidebooks. Many long-standing issues and bugs were fixed thanks to this wonderful Python community.

We had so much activity that I’m still working on closing up issues and pull requests now—weeks after the sprint ended!

After such a tremendous experience this year, I wanted to share with you the things that we’ve learned at pyOpenSci about running beginner-friendly sprints.

What is a sprint like?

If you haven’t been to a sprint before, it’s an experience every open source enthusiast should have. Sprints are where people come together to work on a project. The word sprint can also be used in a professional development setting. This might describe a team of developers working together to release a new feature. For the volunteer open source community, sprints often mean volunteers helping maintainers work on various parts of a project. And it’s important to keep in mind that often the maintainers are also volunteers themselves.

What do people sprint on for pyOpenSci?

pyOpenSci is a nonprofit organization that is devoted to building diverse and inclusive community that supports making science more open and collaborative. Among other things that we do, we run open peer review of scientific Python software.

Running an volunteer-lead open peer review process for software is a challenge. As we grow, it requires infrastructure to support tracking the process. We also create community driven beginner-friendly Python packaging resources and tutorials. High quality learning resources also require maintenance and review. As such, we always need a mixture of packaging experts and those newer to packaging to help catch errors and identify points of confusion.

As the Executive Director and Founder of pyOpenSci, I created most of our pyOpenSci GitHub infrastructure to support our mission. While I cherish times when I can work on technical things, it’s hard to keep up. Mission, vision and community work will always come first.

I really appreciate when community members help us tick off open issues, big and small. These contributions propel the pyOpenSci mission of making science more open and collaborative forward.

Contribution opportunities

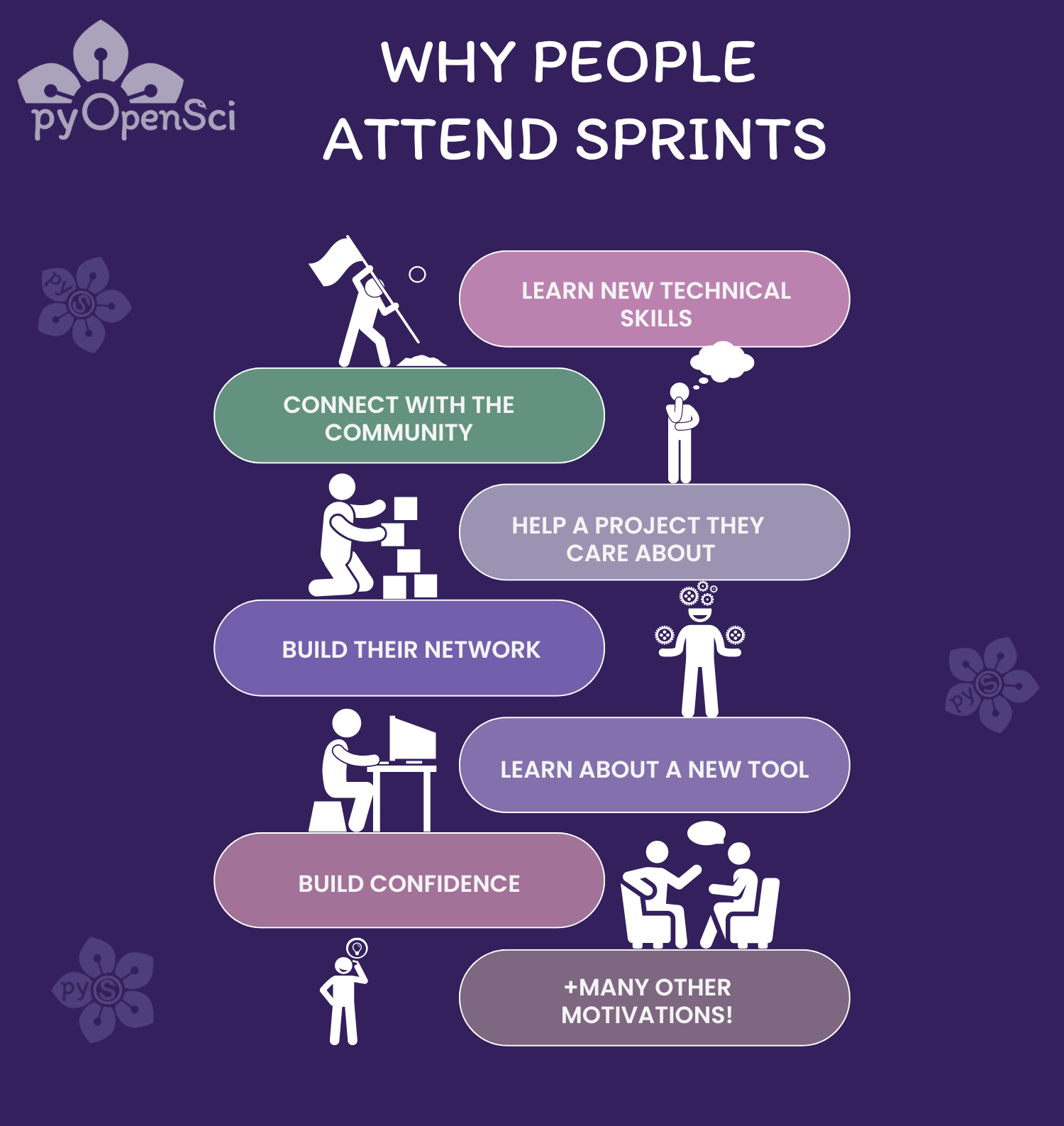

While barriers to contribution are abundant and hard, there are also many opportunities, including:

- Learning and growing skills that may not be accessible in your day job.

- Connecting with other developers, data scientists, and scientists in the community.

- Engaging and being part of an online community or maintainer team.

- Growing your professional network.

- Learning about a new project.

Or, maybe you’re like me —- an Executive Director of a community organization. Coding and development aren’t in my job description, but to teach these topics, I need to keep my skills fresh. And, I love to code. That’s where open source comes into my life!

Barriers in contributing to open source

While sprints are a great way to engage the community in supporting an organization’s (or a project’s) mission, there are many contributor barriers that sprint organizers need to consider.

These barriers include:

- Time to contribute.

- Skills to contribute.

- Confidence in skills / fear of contributing the wrong thing.

- Privilege: This is a loaded one. Open source can’t be diverse if it requires privilege. to participate.

And last but not least:

- GitHub: Using Git and GitHub is always one of the biggest technical barriers that contributors encounter in their open source and data science journeys.

Challenges vs opportunities

So how do we align the challenges that contributors face with the potential opportunities?

While new contributor sprints are not for everyone, and assume some level of privilege in having the time and bandwidth to participate, they can be great for many.

But a sprint will only be a good experience if the contributor’s needs and goals are also considered. Contributors need to gain something from contributing, and this requires:

- time and care in designing the sprint, and

- time spent with newcomers during the sprint.

It’s also important to note that the time required to participate is also a privilege for many, if not most, maintainers who are already volunteering their time to maintain a project! As such we can’t expect all open source packages to be able to support beginner contributions in a comprehensive way.

However, if you do have the bandwidth to hold a sprint that embraces, empowers and uplifts those who are newer to open source, there is a lot to be learned from understanding learner motivations and types. And a few good experiences might mean that a beginner decides to stick around.

Contributing vs learning

The educator inside of me can’t help but align my experience in open source with learner motivations. For me personally, contributing to open source met two of my goals and interests:

- Applied (project-based) learning: I love to learn. Coding and data science are my happy places. But the learning needs to be directly applicable. If it isn’t, I get bored. Moreover, if I can’t see the application of the skill, I have little motivation to learn that skill!

- Student-directed learning: I love to learn on my own time, following my own processes that work for me. Open source allows me to do just that (and without the pressures of a specific deadline in most cases).

If you read the education literature, you will find both project-based learning and student-directed learning to be a commonly discussed topic—especially as it relates to empowering people who are underrepresented in a space.

More on that next…

The power of project-based learning

Project-based learning is founded on the idea that meaningful, applied projects are the best way to teach a topic. This works especially well in the data science space and has been found to be particularly effective with underrepresented groups. In fact, I implemented and collected data on this in a previous project that I designed and ran when I was in academia.

The idea behind project-based learning is that students select a topic they are personally interested in. If they are learning data science, they can find data to analyze and support their project. For underrepresented groups in STEM (and most learners), applied learning resonates because it involves a topic they care about and are motivated to pursue. Skills are learned in the process of achieving a meaningful outcome.

It’s similar to how you can immediately engage a diverse audience in GIS (spatial data) with Google Earth by asking them to zoom into the area where they live (place-based learning).

As a volunteer maintainer of Stravalib, I am motivated to work on Stravalib because I learn in a very applied way.

Sure, a sprint does not have the powerful outcome of a student understanding the impacts of climate change on their local tribal lands. But the concept is the same:

The learning motivation comes from a meaningful outcome that a student wants or cares about.

In leading a sprint, asking the question of “what are your goals for today?” will help you as a sprint leader to direct sprinter efforts down a successful path.

The power of student-directed learning

Every person has different learning preferences. For many years, educators taught people the same way: in a classroom, using the same books and approaches. However, alternatives to this model allow learners to adapt their environment to their personal and learning goal needs. Student-directed learning is based on the idea that people learn differently and have different needs. By creating a hybrid learning environment where students are allowed to pick their learning path and approach, you empower them to own their experience.

Some learners benefit from hands-on demos, whether in a classroom or at the sprint table. They may pick things up quickly or need to watch and digest the demo. Others prefer reading quietly on their own, absorbing information, and trying things out until they figure it out.

If a sprint is set up correctly, learners can parse through available issues. Carefully tagged issues direct them to ones that are beginner-friendly. These issues should not require extensive Git and GitHub expertise, ensuring a good first experience and an early win to build confidence.

Contributors at the sprint can decide if they need direction, mentorship, or just a short tutorial/guidebook for making their first contribution using the GitHub interface.

Collaborative Git and GitHub lessons

This past year, I was awarded the Better Scientific Software (BSSw) Fellowship, in which I proposed lessons on these lesser-known collaborative Git and GitHub skills—the same skills that will support people attending sprints! I am looking forward to having these lessons on hand for next year’s sprints, in order to support those who are still fighting to learn Git and GitHub (it can be an uphill process!).

The anatomy of a pyOpenSci sprint

Based on my understanding of the learning motivations and challenges that new contributors face, I’ve developed a pyOpenSci sprint approach that I’ve found to be successful in empowering new contributors to make their first contributions.

Create opportunities for first-time contributors

When someone joins your sprint, start by asking:

- What are you looking to achieve today?

- How comfortable are you with Git and GitHub?

If the contributor is new to Git and GitHub, it can be empowering to direct them to review documentation with a fresh perspective. In our pyOpenSci sprints, beginners often find bugs and issues in our online packaging tutorials. Fixing these bugs is empowering for new contributors and helps pyOpenSci curate useful, current, and beginner-friendly content.

If you have a package, let the user review your tutorials or docs. They can then either open issues or pull requests to address the issues.

The beauty of documentation reviews is that any issues and PRs submitted can be done entirely using the GitHub interface. This is a true win/win for both the maintainer and the contributor.

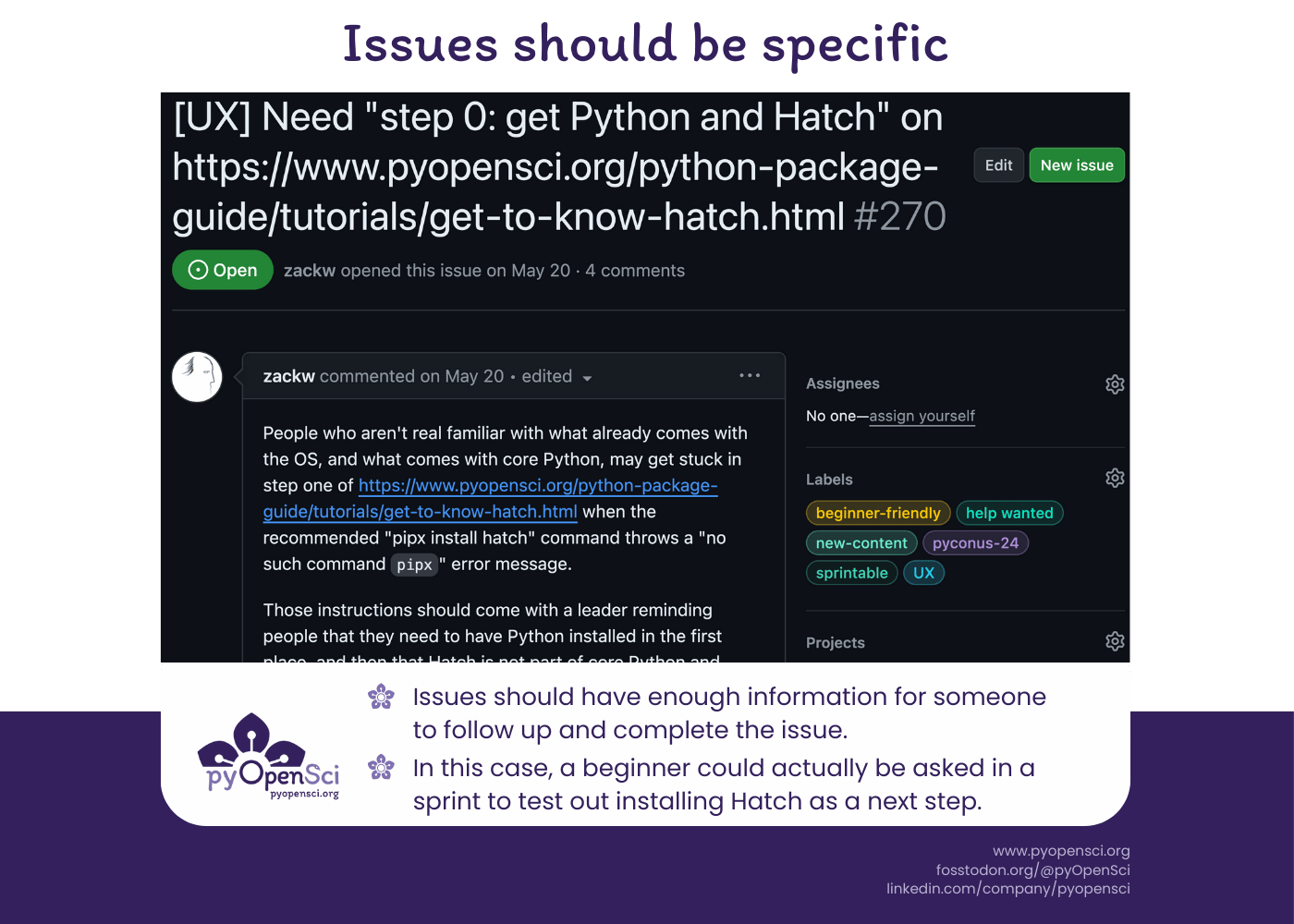

Write useful constructive issues

A good sprint begins with useful, labeled issues. The information in the body of an issue is critical. Be sure to include the specific details of the issue to be addressed with the lens of someone who is new to your project. Give potential contributors everything they need to start working, which helps reduce administrative questions during the sprint. For a table of 10-20 people sprinting for pyOpenSci, this means the sprint leader will have fewer questions to answer during the sprint event.

Label issues as help-wanted and/or sprintable

You never know when a contributor might be looking for a data science project to

work on. It’s always helpful to tag issues that could be completed or started

during a sprint as sprintable and help-wanted if you think someone outside

of your team could tackle the issue. This tip came from

Inessa Pawson, who has extensive experience

with contributors through her work on the

Contributor Experience Project.

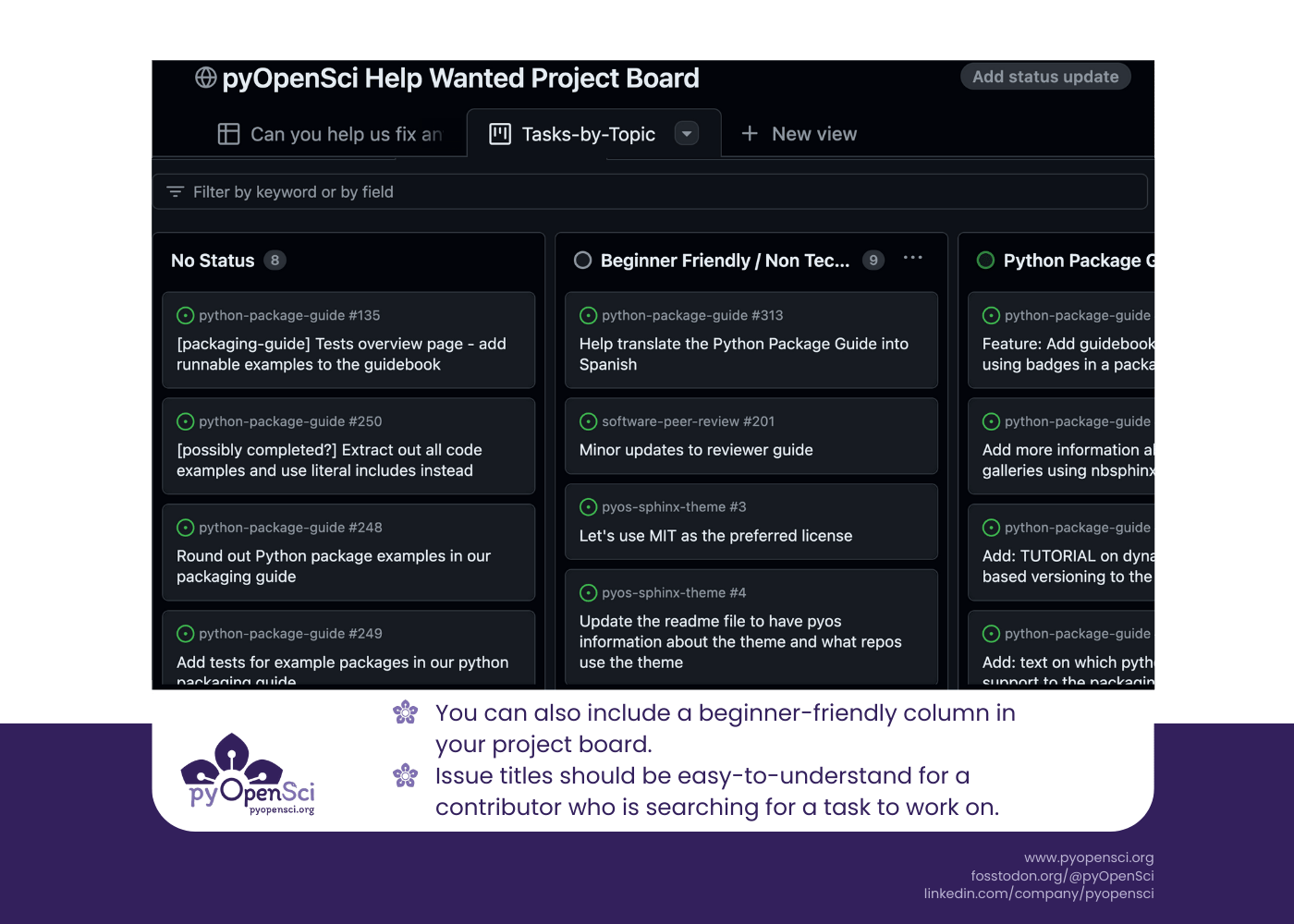

Collect issues in a single place—the help-wanted board

Curate a help-wanted board that contains all the issues that could be completed

by an outside community member in one place.

Our pyOpenSci help-wanted board is a

GitHub project board

that allows us to organize issues that we think others could work on by type,

including:

- Beginner-friendly

- Python

- DevOps / CI

Infrastructure and automation of issues

PyOpenSci has many GitHub repositories where people might label an issue as

help-wanted and forget to add it to our sprint help-wanted project board. To

address this, we set up

a CI workflow

that can be added to any repository. This workflow moves any issue labeled

sprintable or help-wanted to our help-wanted GitHub project board.

GitHub project boards support project workflows that auto-add issues to a project board with a specific label. However, our GitHub organization’s open source subscription only allows for one project workflow of this kind associated with one repository, which is why we set up the GitHub action. We also have things setup so an issue is removed / archived from the GitHub project board once it is closed.

Make it truly beginner-friendly

To support beginners contributing to open source, consider having one or two helpers (depending on the size of your sprint) who can assist with:

- Understanding the issues

- Using Git/GitHub

- Directing novice sprinters to beginner-friendly items

In all of our sprints to date, we have had a mixture of people who:

- Know Git and GitHub but haven’t contributed to open source before. Sometimes these people are developers and can tackle coding challenges!

- Are seasoned and just need enough information in the issue to be successful (see above section on issue content).

Other times, you have people who really want to contribute but are uncomfortable with Git and GitHub and have never contributed to open source. These people will be incredibly empowered if you can create a smooth path to their first contributions.

Wrap up

Well-led sprints offer both new and seasoned contributors an opportunity to contribute to a project, while also learning new skills, connecting with new people, and learning about new projects. If you plan to support new contributors in your sprint, then it’s ideal to do some legwork before the sprint begins to ensure sprint attendees feel supported and have the help that they need when they get stuck.

pyOpenSci is looking forward to our next sprint—to be held at the SciPy 2024 meeting in Tacoma, Washington. Last year we had three people make their first contributions to open source in our SciPy 2023 sprint. I’m hoping that this year is even better!

Come join us if you are there!

Leave a comment