TL;DR

- pyOpenSci lead 3 incredibly successful events at SciPy this year: A tutorial, a talk and a 1.5 day sprint.

- During our SciPy 2024 meeting sprint we had over 35 GitHub issues and pull requests submitted by XX new contributors.

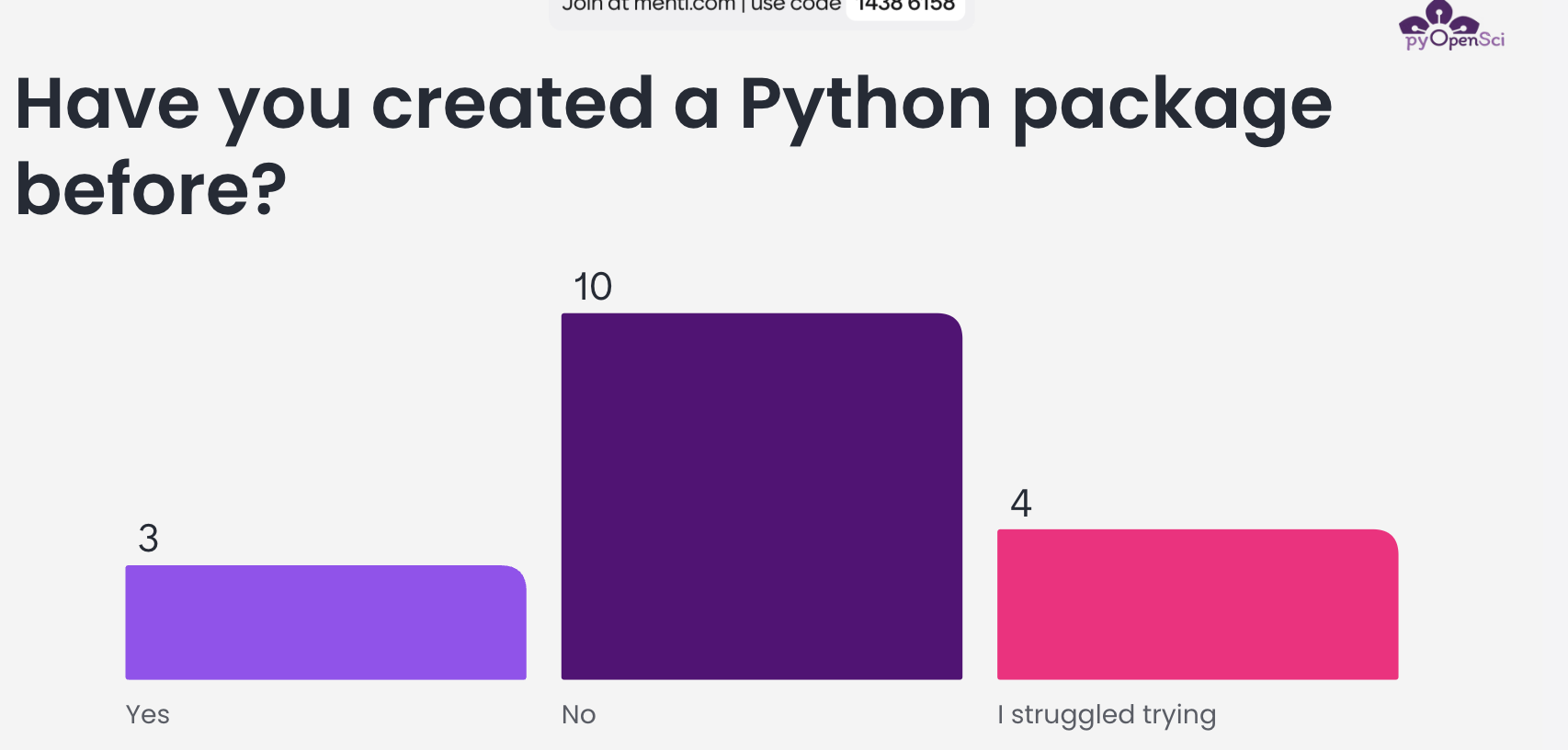

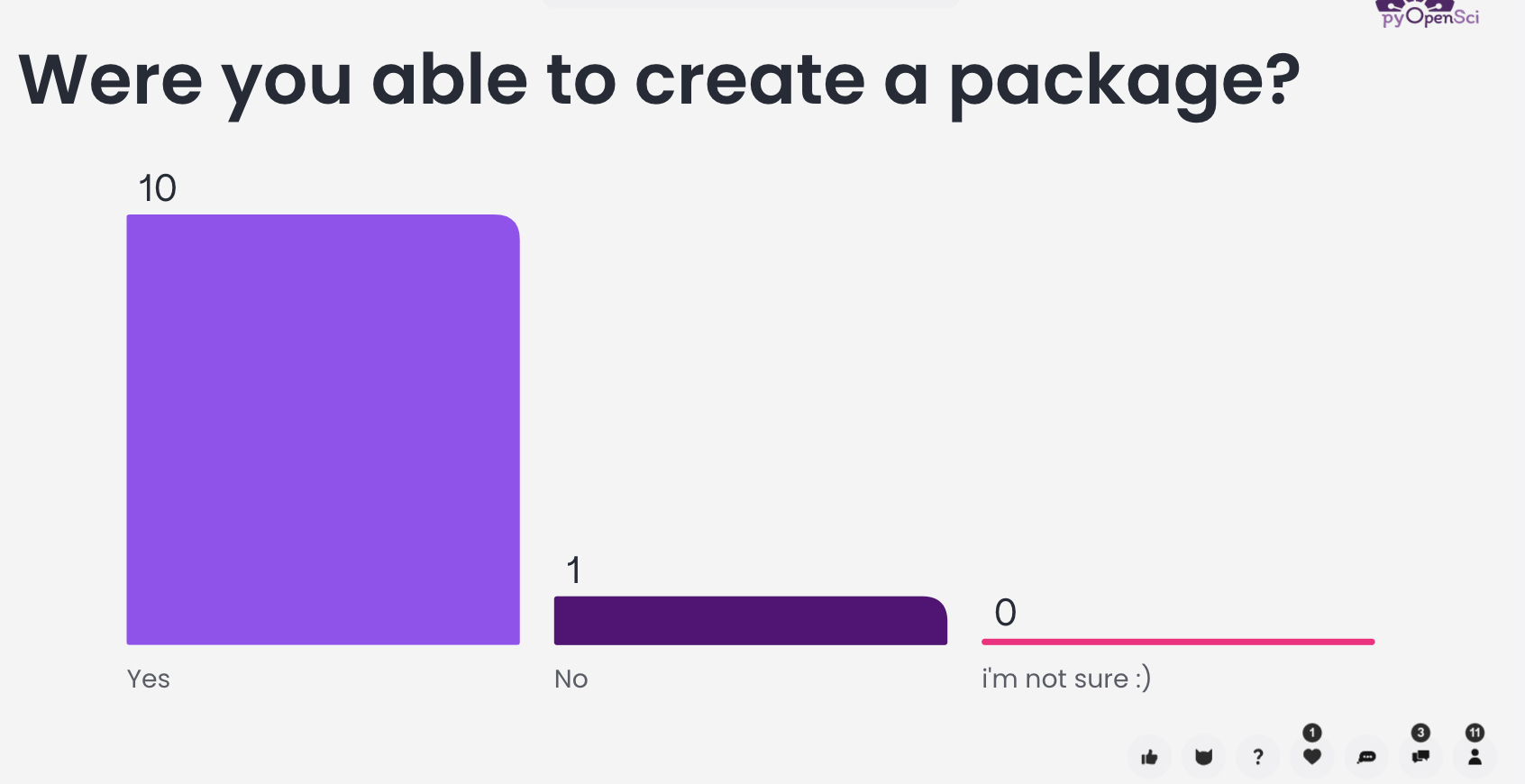

- Our tutorial had over 30 attendees. Almost all of the learners had never created a Python package before, and most of them were successful creating their first Python package.

- I thoroughly enjoyed connecting with new and old colleagues and friends.

pyOpenSci’s fourth year attending SciPy - my experience

This year was my fourth time attending the annual SciPy meeting—a meeting organized by NumFocus that celebrates the scientific Python ecosystem. My first experience was in 2019, where we held the very first pyOpenSci Birds of a Feather (BoF) session.

A Birds of a Feather session, also known as a BoF, is a community-organized event where people lead a discussion around a specific topic. Our 2019 SciPy BoF was about our peer review process, which we had just launched that year.

One of the biggest differences this year has been how much pyOpenSci has grown, which means we saw many familiar faces, including:

- Maintainers of packages that we have reviewed and accepted through our scientific Python software peer review process,

- Colleagues who I have met at other meetings, such as PyCon,

- Reviewers and editors from our community,

- Members of our advisory council, contributors, and

- Friends—so many friends.

This year, I was busy at SciPy, and spent my days:

- Running an in-person tutorial: Create Your First Python Package.

- Giving a talk, The power of community in solving scientific Python’s most challenging problems, in the Maintainers Track (what an honor!).

- Working the hallway track.

- Running a 1.5-day sprint that resulted in over 35 issues and pull requests. Wow.

Admittedly, I started off this conference behind and frazzled. You see, pyOpenSci has been growing in recent months. With that growth comes more wonderful people to support and engage with! More people getting involved does mean more work for pyOpenSci. However, the time is worth it, as all of this effort is moving pyOpenSci’s mission of supporting open science forward.

In the end, even though I wasn’t quite as prepared as I wanted to be, my talk and the workshop went great! This was a lesson for me in understanding that things can be less than perfect and still go well.

More on all of that below. But first–what is the SciPy Conference?

A brief history of the annual SciPy conference

If you haven’t attended this meeting before, let me give you the rundown. The SciPy Conference is an annual event dedicated to celebrating and learning more about scientific computing, all using the Python programming language. The meeting started back in ~2002. The early meetings were run by EnThought and were smaller in size and scope. Over the years, SciPy has evolved significantly, mirroring the 🚀 explosive growth of the Python ecosystem 🚀 in scientific computing and data science.

Today the SciPy Conference, hosted by NumFocus, attracts over 700 attendees from diverse scientific fields such as astronomy, biology, geophysics, and more. SciPy is much more than just a meeting.

SciPy features:

- Incredible keynote speakers, such as the inspirational Carol Willing.

- Talks from the community about tools and approaches.

- Poster sessions that allow presenters to directly engage and discuss cool work with the meeting attendees.

- Tutorials led by community members (including pyOpenSci) that cover important scientific data processing and analysis-related Python skills.

- Sprints: collaborative coding sessions where people come to contribute to and learn about open-source projects.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the lightning talk sessions. During lightning

talks, people throw their names into a literal bucket. If their name is selected,

they are given 5 minutes (or less if the dice are rolled) to talk about a topic

they love. Last year the talks featured a large stuffed dice that you would roll. the number that was rolled determined how much time you have to present and what distractions the moderators would apply to you. ![]()

You see, at SciPy, there are often off-beat distractions from the moderators along the way, such as the infamous grab claw (see below). Yes, it is as ridiculously hilarious as it sounds.

Did someone mention sharks? More here on my experience last year giving a SciPy lighting talk.

Another cool thing about SciPy is that the entire meeting is community-driven. The scientific Python community really shows up to make this meeting what it is. All of the sessions are volunteer organized and run. Volunteers also spend considerable time engaging with presenters, ensuring there are social activities that everyone is invited to in the evenings, and generally making sure that everyone feels included.

Since the pandemic, the SciPy meeting has adapted to support virtual/hybrid participation, which has further increased its reach. In fact, some remote attendees also helped organize the meeting!

If you are a Pythonista who loves science, this meeting is for you!

pyOpenSci’s first SciPy tutorial was a huge success: Create your first Python package

My adventure at the SciPy meeting kicked off with a 4-hour tutorial entitled: Create Your First Python Package: From Code to Module.

I have to start by saying the tutorial went great. Here is what one person had to say about it:

The content and the crew! The team was so kind, patient and approachable. I appreciate the amount of support and reassurance given during this tutorial. The content of the tutorial was also spot on. Everything we covered felt relevant and useful, and gave me the confidence to feel capable of creating my own packages.

This tutorial was an expanded version of the Create Your First Python Package tutorial that pyOpenSci ran in April 2024. In our first workshop, we had over 20 people create their first Python package. We had similar success in our SciPy tutorial.

I realized when I got to SciPy that I hadn’t actually taught in person since 2020! I vividly remember the last in-person class that I led for the Professional Graduate Program in Earth Data Analytics that I created at CU Boulder. That class happened on the Wednesday before the pandemic lockdown started in the United States. It was a sad day to say “goodbye for now” to in-person teaching and to my students. Teaching and working with learners is, after all, one of my favorite things. However, luckily we had been running the program using a hybrid online and in-person approach, so the transition was sad, but didn’t impact our learners too much.

But back to SciPy, it was a rush to be back in the “classroom” at SciPy 2024!

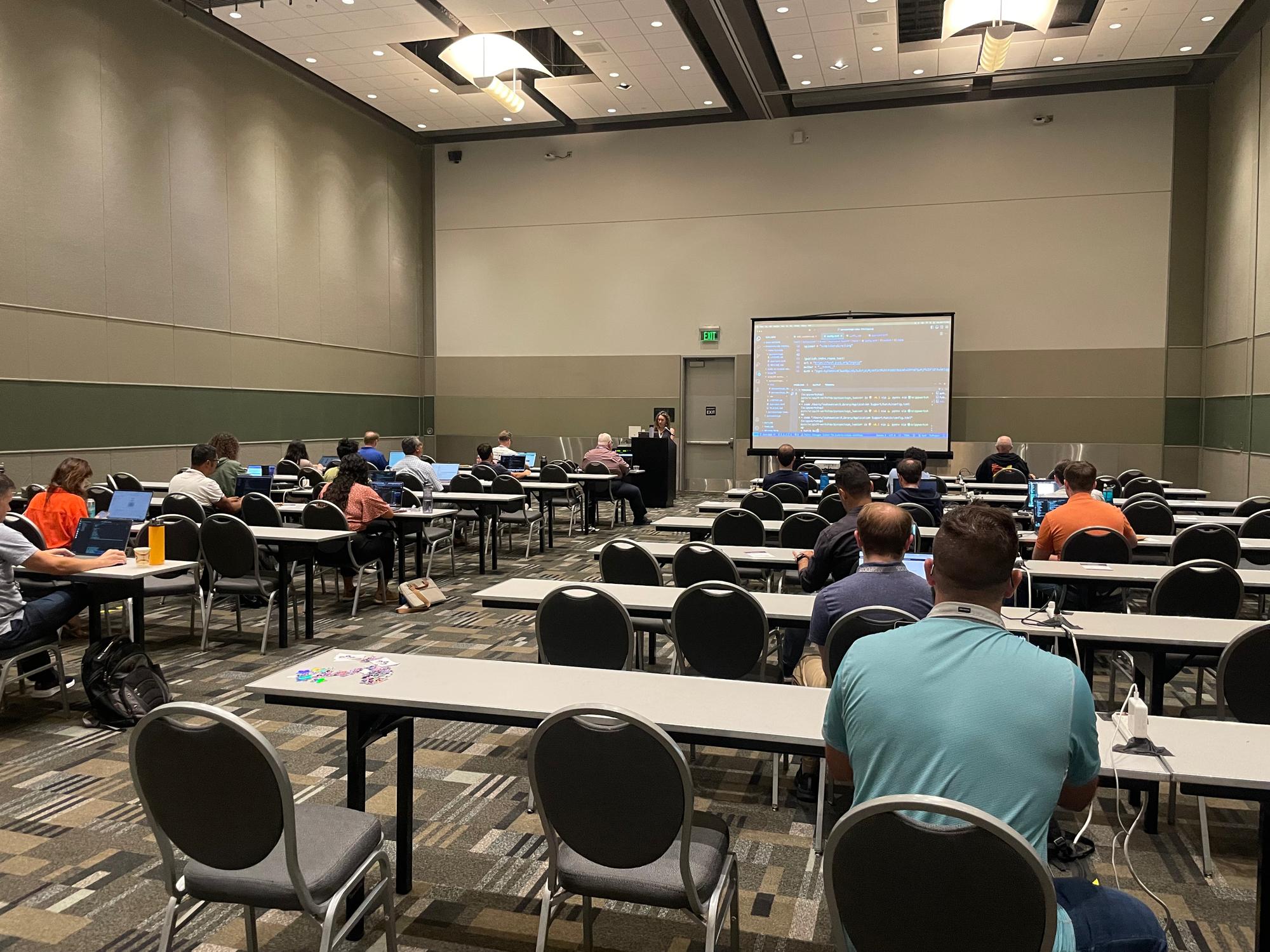

A pyOpenSci tutorial room full of eager learners and tech that worked

Our workshop room was full of people eager to better understand Python packaging. We also had great helpers, and all the tech in the room just worked seamlessly. The SciPy tutorial organizers did an amazing job of ensuring everything ran smoothly.

After a really tricky internet situation at PyCon this past May, I truly appreciated the smooth setup of the room.

A special shout-out to pyOpenSci community members Jeremiah and Isabel Zimmerman, who were committed to helping all the learners have a successful experience. Their support and expertise were invaluable.

pyOpenSci is helping the community navigate Python packaging challenges together

Of course, there were a few challenges, too.

-

Many participants came without working through the setup instructions. This was particularly problematic for those with government-issued laptops, where they couldn’t install software.

-

While most workshops could use the Jupyter-Hub cloud platform called Nebari, hosted by Quansight Labs, it didn’t support our development use case. Thus, we didn’t have a “backup” platform for participants who couldn’t get things set up. However, I later worked with Sarah Kaiser from GitHub, who set us up with a Codespace that we can use for future workshops.

-

Because we practiced publishing to (test) PyPI, we should have suggested that participants create an account in advance!

-

Installing things across operating systems (Linux, Mac and windows) is always tricky. In this workshop, we switched from suggesting pipx to using Hatch installers for Mac and Windows users. We made this change because Windows users previously had significant issues installing

pipxboth during our previous workshop, and during our PyCon 2024 sprint.The glitch we encountered this time with the installers was that Hatch would initiate an update on some computers that already had it installed when users ran

hatch --versionfor the first time. This is something we need to address in the future, or at least warn users about.

Our pyOpenSci tutorial at SciPy 2024 was hugely successful

Challenges aside, we also had a lot of successes to celebrate!

Similar to our online workshop in April, many attendees created their first Python package!

The verbal feedback from participants was overwhelmingly positive. Comments like

“One of the best workshops I’ve been to”

and

“I’m always behind in workshops like this. This was the first workshop where I could actually keep up”

made all the effort worthwhile.

Needless to say, I left the event with a full heart. 🫶

Several participants enjoyed the process so much that they joined our sprint afterwards to help build out the packaging guide. More on that below.

pyOpenSci, Python packaging and community–my talk at SciPy 2024

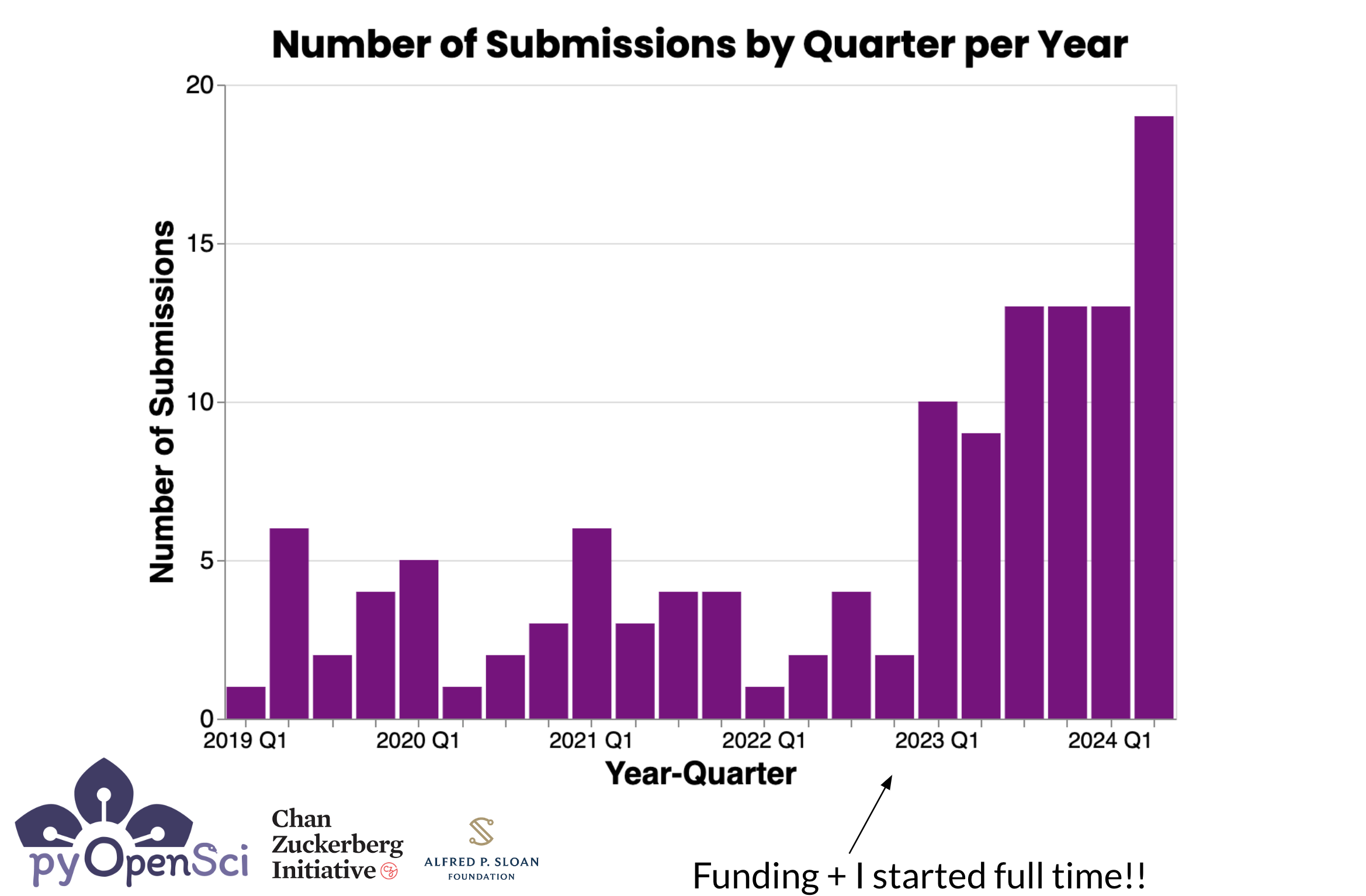

The day after the workshop discussed above, and the first day of the conference, I gave my first-ever talk, The power of community in solving scientific Python’s most challenging problems, in the maintainers track at SciPy.

What an honor to be selected as a speaker.

This year, the SciPy maintainers track was organized and hosted by Inessa Pawson, Brigitta Sipőcz, Matt Craig, and Mridul Seth. It kicked off with a fantastic talk by Eric Mah. Eric discussed how he has been bringing open-source values and workflows to the corporate environment at Moderna (yes, the same company that makes one of the more popular COVID vaccines). Eric’s talk carefully navigated both the benefits of open source for corporate teams while also acknowledging some of the tensions.

My talk closed out the session.

pyOpenSci is leveraging and working with the community to solve scientific Python’s challenges

My talk was about how pyOpenSci has been carving out space and coordinating community efforts to address several core challenges in our scientific Python ecosystem. These include:

- Helping scientists find and use the right open-source tools.

- Encouraging scientists to write better code, share their code, and build better software.

- Ensuring scientists get credit for their open-source work.

- Addressing the ongoing challenges of packaging in the Python ecosystem-—a topic I discussed in my PyCon talk in April, which is also available on YouTube. I’d love for you to check it out!

pyOpenSci’s Python packaging guidebook is having a positive impact on the scientific Python ecosystem

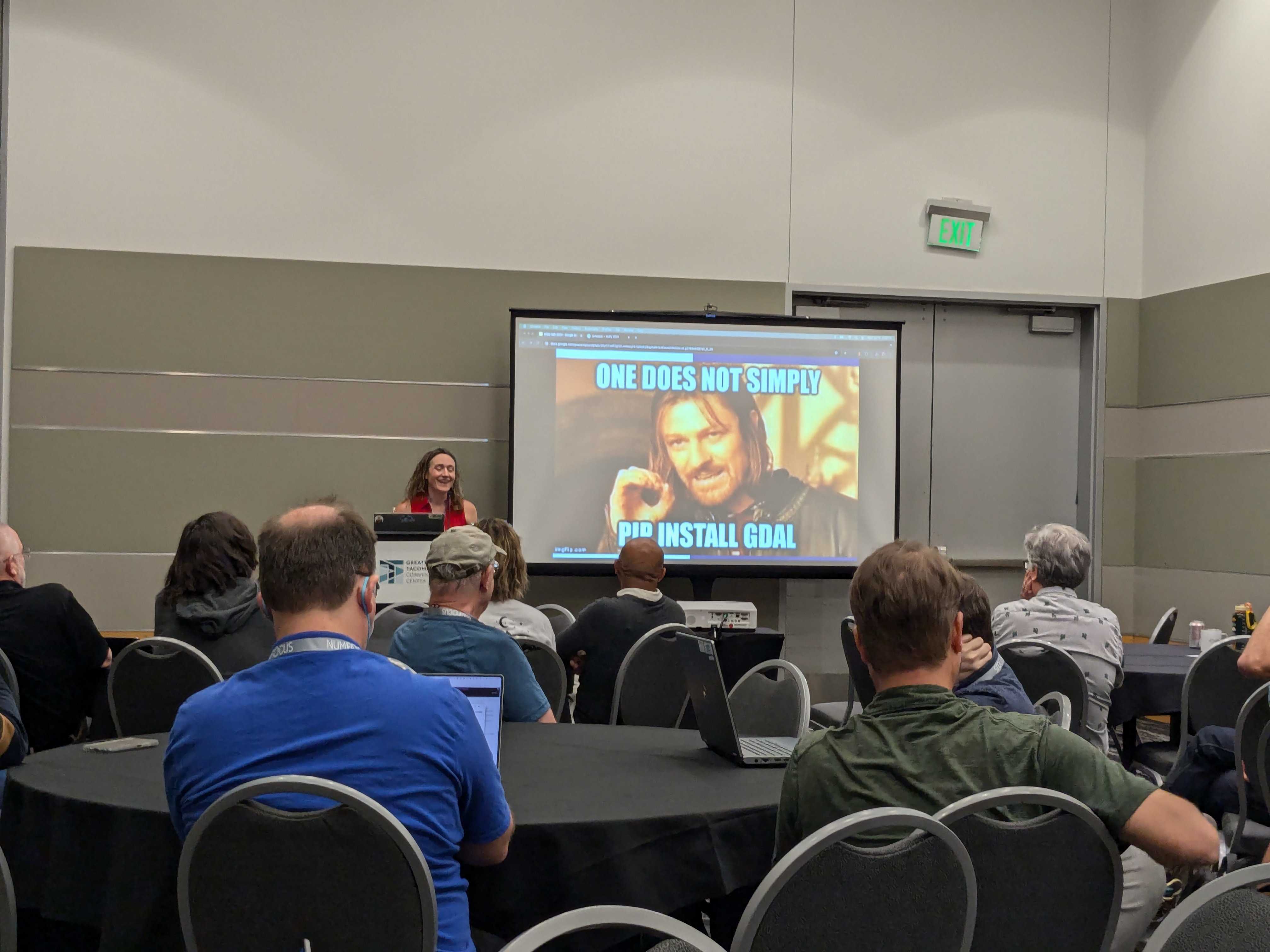

During my talk, I addressed critical pain points I’ve experienced as an educator teaching spatial and earth data science, and as a maintainer of stravalib—a package that supports my pre-getting-COVID obsession with ultra mountain running.

Things kicked off with a bang, thanks to the best meme ever, created by Filipe Fernandes. Filipe, a conda-forge maintainer, introduced me to conda environments when I was struggling with creating consistent spatial data environments for my students. Anyone who’s spent time wrestling with GDAL in a Python environment knows the struggle. Thanks to folks like Filipe and the conda-forge community, managing spatial environments has become much easier for everyone!

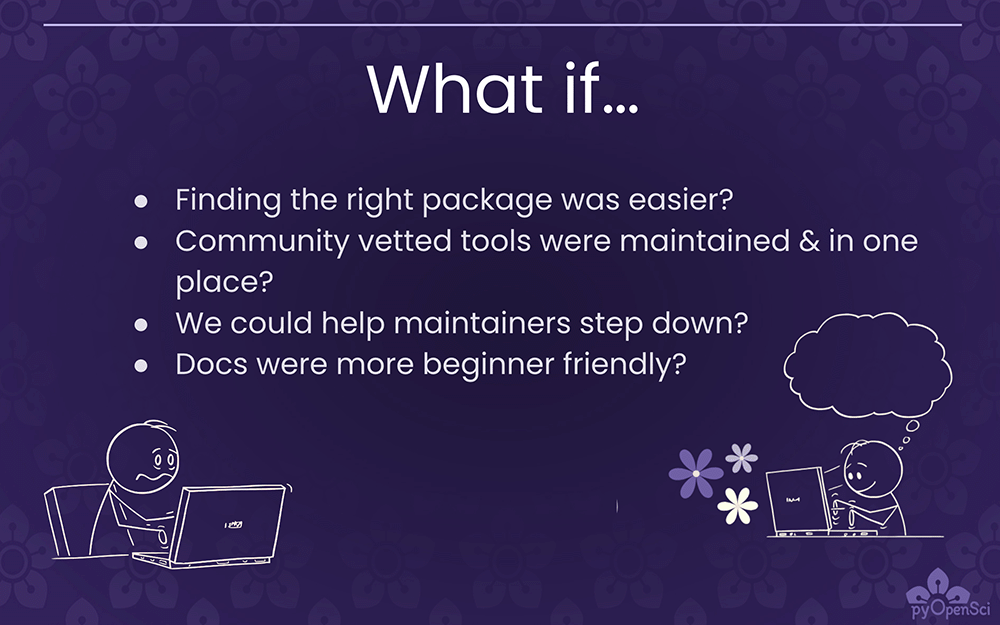

I discussed how pyOpenSci is working to make things easier for scientists by improving access to the right packages, maintaining community-vetted tools in one place, helping maintainers step down and transition out, and making documentation more beginner-friendly.

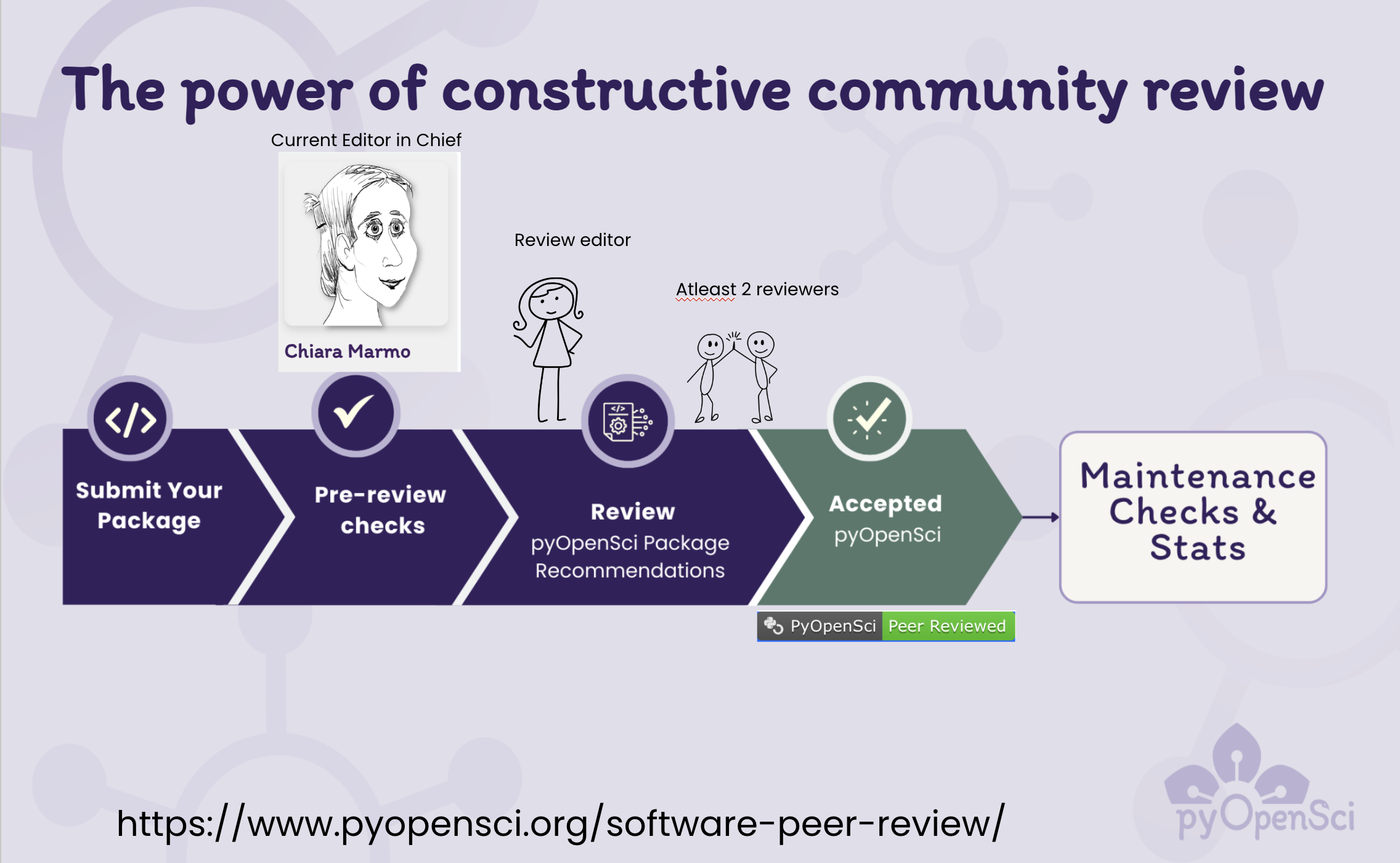

pyOpenSci is running community-led inclusive, open software peer review

I also talked about how pyOpenSci is using an inclusive, community-led peer review process to achieve several goals:

- Helping scientists find vetted, trusted, and maintained software.

- Helping scientists build better software.

- Providing maintainers with credit for the important work they do to support open science.

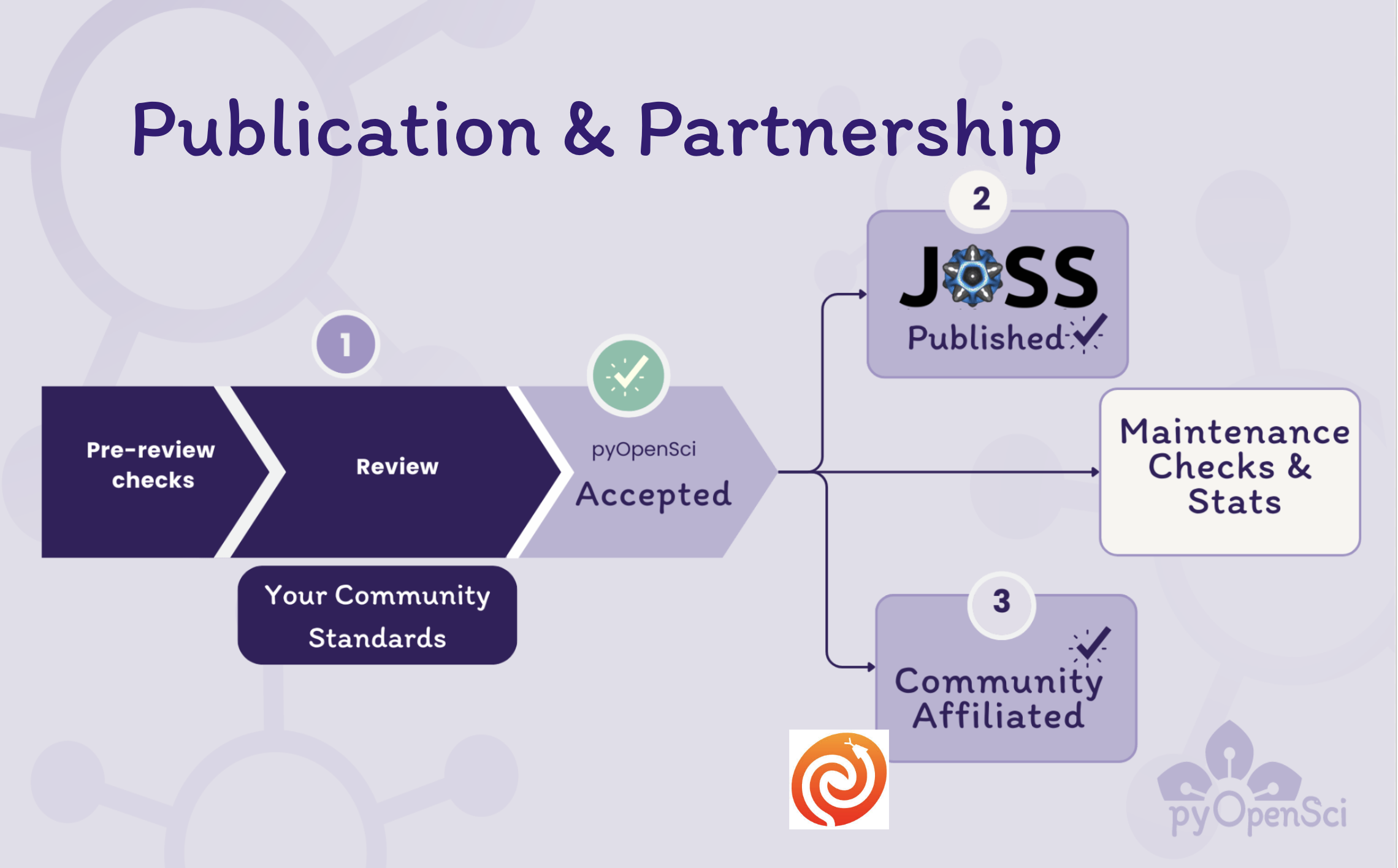

I also discussed how pyOpenSci partners with communities like the Journal of Open Source Software and Astropy to leverage resources. In the spirit of open source, our goal is to learn as much as we can from other communities.

Where ever we can, pyOpenSci partners with other communities and leverages their work. Building on top of and leveraging each other’s work IS the true spirit of open source and open science. By working together, we can move forward together.

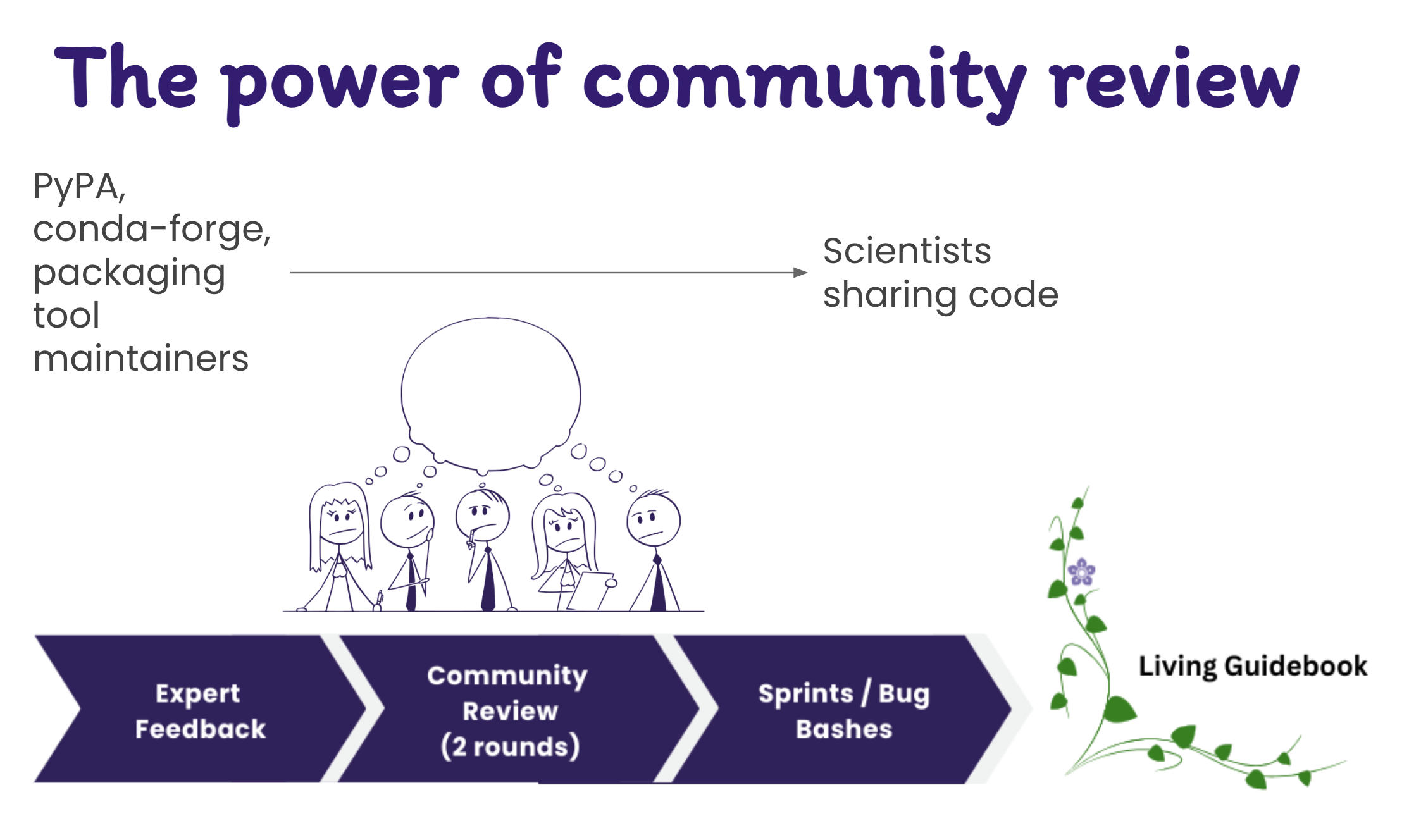

pyOpenSci and how we created a truly community-driven Python packaging guidebook

I also discussed our work in the Python packaging ecosystem, specifically around making packaging more beginner-accessible and friendly. pyOpenSci leans into community expertise and review as a way to leverage community expertise when making packaging decisions. People who have reviewed our packaging content include both those in the scientific Python ecosystem and those working on core Python challenges. These people include:

- Python Packaging Authority members (PyPA)

- Packaging tools maintainers

- Packaging experts

- Scientists

- People new to packaging

All of these people have helped pyOpenSci create a Python packaging guide that is both accurate and beginner-friendly.

One of the decisions we made as a community early on was to use Hatch as an end-to-end packaging tool. We believe Hatch is user-friendly and supports many of the use cases scientists have when sharing their code.

I met some great people and had good discussions about peer review and Python packaging. The presentation will be on YouTube at some point, and I will update this post with the link when it’s live. In the meantime, my slides are available on pyOpenSci’s Zenodo community.

pyOpenSci and reconnecting with the scientific Python community–the hallway track

It seems like this year has been the year of the hallway track. The hallway track refers to the time spent in the hallways of a meeting, talking to people you don’t normally get to work with in person. Sometimes, the hallway track can be even more valuable than attending the talks. You can always watch the talks later on YouTube, but you can’t always collaborate in real life like you can at a meeting like SciPy, which attracts people from around the world.

I spent a lot of time talking with colleagues, friends, and community members about all things Python, open source, and open science.

- I worked with Sarah Kaiser on our new GitHub container to support workshops.

- I had an ad hoc sprint with Angus and Rowan from the MyST Markdown community to develop our pyOpenSci peer review metrics dashboard.

Additionally, I caught up with colleagues, chatting about packaging and scientific Python.

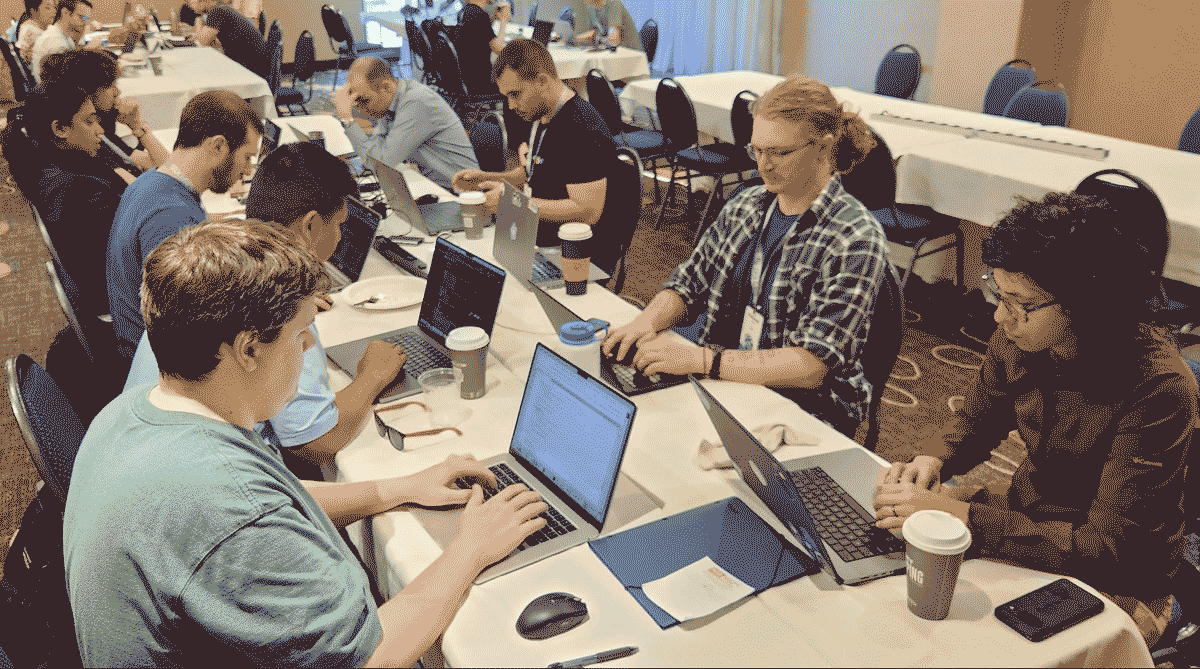

pyOpenSci sprints at SciPy–over 39 pull requests and issues

Every year at SciPy, we spend the last two days of the meeting sprinting. This year was the first time I stayed for both days of the sprints.

A brief overview of open-source sprints

If you haven’t been to an open-source sprint before, a sprint is an open session where contributors join a project and help address specific issues and tasks that the project needs help with. I wrote more about how pyOpenSci runs beginner-friendly sprints here.

Sprints are a lot of fun because, given enough time, you can make significant progress on a project and support first-time and new contributors in making their first contributions!

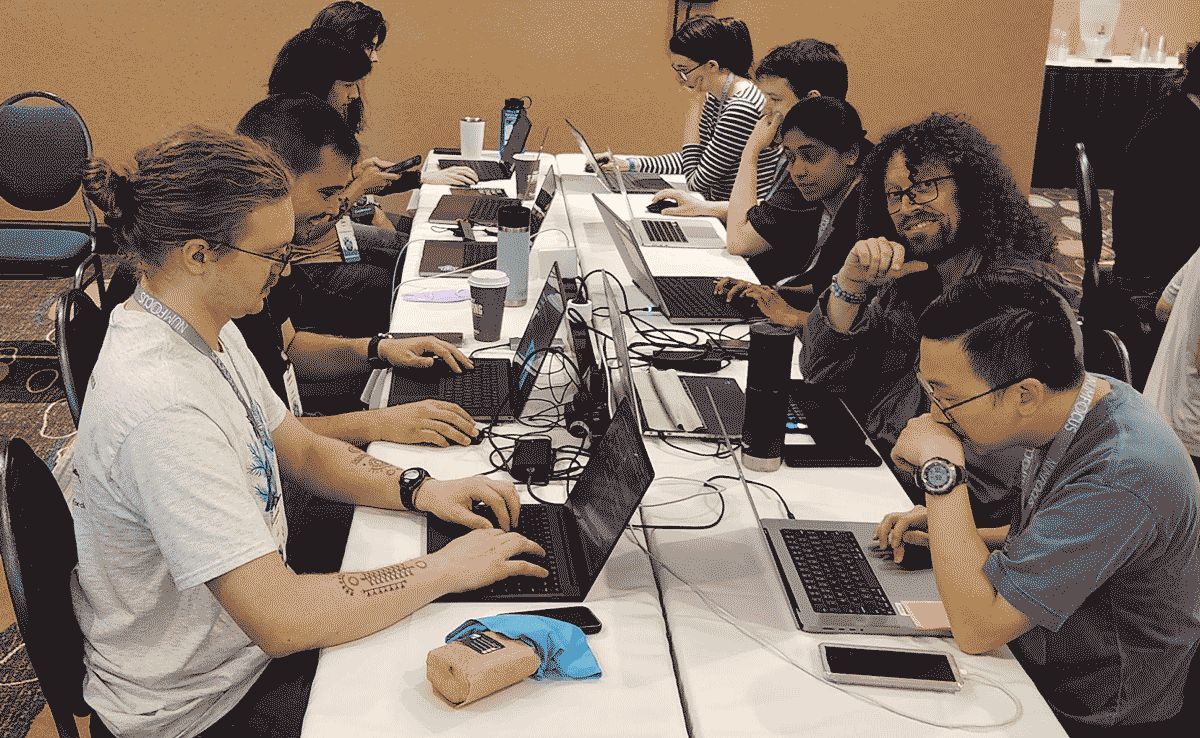

This is what the second sprint room looked like this year at SciPy. There was a scramble to find a new location for our sprints due to some power issues stemming from an unexpected accident in Tacoma. Our space was much smaller than usual, but we made it work!

We had a great group this year who worked on a variety of tasks, including:

- Tackling a longstanding issue to sync our labels across all repositories. We have many labels, and they vary across repositories. The work is now done, and next, we will implement a GitHub action to clean up labels across all of our GitHub repos.

- Working on our Python Packaging Guide, which is now being translated into Spanish!

- Someone enthusiastic about Sphinx worked on our pyos-sphinx-theme. pyOpenSci has several online “books” that would benefit from using the same theme and colors that follow the pyOpenSci brand.

- A handful of people contributed to our MyST Markdown peer review metrics dashboard.

Several people made their first-ever contributions to open source during our pyOpenSci sprints, which was fantastic. We had a lot of great people get involved and support us. The positive vibes were contagious!

pyOpenSci’s most successful SciPy meeting yet, and we’re just getting started

It’s amazing to think about how far pyOpenSci has come in the past five years. In 2019, pyOpenSci was just kicking off its peer review process, and only a small number of people knew about us. By 2023, we had some funding to begin traveling and spreading the word about our work, but we were still somewhat unknown in the community. Fast forward to 2024, and people not only know about us but are also excited to contribute and support our mission. We aim to help scientists find and build better software and develop better open science skills.

After this spectacular year, I can’t wait to see what 2025 brings!

Get involved with pyOpenSci

If you are interested in getting involved with us, there are many ways to do so! Check out our volunteer page as a starting place. Or shoot an email to media at pyopensci.org.

I can’t wait to see you next year at PyCon US and SciPy 2025!

Connect with us!

There are many ways to get involved if you’re interested!

- If you read through our lessons and want to suggest changes, open an issue in our lessons repository here

- Volunteer to be a reviewer for pyOpenSci’s software review process

- Submit a Python package to pyOpenSci for peer review

- Donate to pyOpenSci to support scholarships for future training events and the development of new learning content.

- Check out our volunteer page for other ways to get involved.

You can also:

- Keep an eye on our events page for upcoming training events.

Follow us on social platforms:

If you are on LinkedIn, check out and subscribe to our newsletter.

You can also:

- Check out our Python Package Guide for comprehensive packaging guidance

- Keep an eye on our events page for upcoming training events

Leave a comment